1 Introduction

Quantum information processors exploit quantum resources to perform both quantum communication (QC) and quantum computation tasks that are applicable to various practical applications. While these are two distinct pillars of quantum information technology, they are deeply interconnected. QC focuses on transmitting quantum states with unconditional security, examples include quantum key distribution (QKD) [1, 2], quantum teleportation (QT) [3, 4], quantum secret sharing (QSS) [5, 6], quantum secure direct communication (QSDC) [7, 8], and quantum dialogue (QD) [9, 10]. Quantum computation, on the other hand, exploits quantum superposition, entanglement, and interference to perform computational tasks with potentially exponential speedup over classical systems for certain problems, e.g., Shor’s algorithm for factorization [11] and Grover’s search algorithm [12], with applications in optimization, secure computation, machine learning, and cryptography. In the sixth-generation (6G) context, QC can provide information-theoretic security against quantum-capable adversaries [2, 13, 14], while quantum computation can optimize network resource allocation, traffic scheduling, and distributed AI model training. Hybrid quantum networks, where QC links provide secure interconnects for distributed quantum computing nodes, are expected to form the backbone of the future quantum internet [15, 16].

Over the past four decades, several applications have been designed, among which the QKD [1, 2] stands out as a well-known application. Besides QKD, there are several QC protocols [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. Similarly, there are many quantum computation tasks, such as quantum private comparison [17], blind quantum computation (BQC) [18], quantum voting [19], and the field of quantum e-commerce [20] that includes computation tasks such as secure transactions, optimization problems, and recommendation systems. Initially, these protocols were designed for two-party scenarios in their original form, but later, researchers have extended these two-party communication/computation protocols to their respective multiparty regimes with the prime intention to extend a particular task on a large-scale network that can efficiently work among the n number of end users (quantum/classical). Specifically, these multiparty protocols serve for various practical applications on a large scale and are required to fulfill the mission of building global-scale quantum networks. Such global-scale quantum networks incorporate non-terrestrial components as an essential element. In a realistic scenario, the commercial realization of such quantum network applications relies on their compatibility and integration with existing fifth-generation (5G) or upcoming 6G technology [21], where the utmost concern for advancing and developing quantum protocols is evaluating their performance in terms of unconditional security, privacy, required resources, and scalability. Addressing the core problems of 6G, such as quantum-enhanced security and trust, ultra-reliable low-latency coordination, extreme spectrum utilization and interference management, integrated sensing and communication, global time and frequency synchronization, and distributed AI/edge intelligence, will require a combined approach where QC ensures end-to-end security, and quantum computation provides the computational power to manage and optimize the network at scale [22, 23].

In this article, we briefly discuss those concerns and summarize our contributions as follows:

-

We cover some characteristic features of QC systems and their specific applications. We begin with a general perspective of achieving unconditional security in QC, and then we briefly discuss applications, such as QKD and QSDC, along with their semi-quantum versions. Additionally, we discuss various multiparty quantum computational tasks.

-

Later, we aim to explore the role of non-terrestrial networks (NTNs) in QC applications and discuss that employing quantum entangled resources to NTNs enables trusted repeater-based quantum networks to establish a global space-based QC infrastructure, thereby advancing to facilitate the realization of connecting quantum cities.

-

We explore the role of QC in 6G technology, aiming to highlight its integration into 6G communication infrastructure which enhances the communication rates and computation capabilities, leveraging quantum advantages. Quantum technologies can help 6G networks overcome peak traffic periods by pooling resources during off-peak periods. For example, superdense coding (SDC) can double the transmission rate, thus reducing congestion on 6G communication networks.

-

This article explores the prospects of QC within future 6G networks and presents numerical simulations to demonstrate the potential of SDC to boost data transmission rates. Specifically, we use a system-level simulation to examine resource utilization in 6G quantum networks under varying traffic loads, highlighting how SDC can improve transmission efficiency during periods of high demand. We simulate four scenarios to illustrate resource utilization for different traffic demands (TDs). Our results show that high TDs exploit the communication rate advantage of SDC, while low TDs reserve the entanglement distribution (ED) for future QC applications. This dual benefit, i.e., improving network efficiency while strategically managing entanglement resources, provides new insights into the role of QC in 6G traffic engineering. ED refers to the process of sharing entangled quantum states between distant nodes in a quantum network, enabling protocols such as QT and SDC.

Our manuscript is organized as follows. We start with a brief introduction of the field and context in Sect. 1. In Sect. 2, we describe characteristic features of QC followed by the role of NTNs in QC in Sect. 3. In Sect. 4, we describe how QC can play a vital role in 6G networks. Furthermore, we describe our system model and discuss our simulation results for four different scenarios in Sect. 5. We ultimately conclude in Sect. 6.

2 Characteristic features of QC systems

We discuss two distinctive features of QC systems that not only provide information security and quantum advantage, but also lay the groundwork for the future quantum internet. The first and most significant feature is the “unconditional security” against a malicious adversary, achieved by QC systems. The second feature we discuss is the “multiparty quantum computation,” which involves a network of interconnected quantum computers (distributed quantum networks) facilitated by QC channels. This feature underscores the integral role of QC systems in multiparty quantum computation, essential for various tasks crucial to the development of a futuristic quantum internet [15, 16].

2.1 Unconditional security in QC

In QCs, quantum cryptography is a thriving research field known for its hallmark of unconditional security rooted in the fundamental principles of quantum mechanics. Unconditional security refers to the system being information-theoretically secure against any attack, regardless of the adversary’s computational power or resources (quantum/classical). The key pillars, namely Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle (HUP), no-cloning theorem, properties of quantum entanglement, and superposition principle, collectively form the foundational basis guaranteeing unconditional security against eavesdropping. As the first pillar, HUP plays a pivotal role in ensuring security through conjugate coding, a technique where information is encoded in conjugate pairs of two mutually unbiased bases (MUBs), e.g., computational and diagonal bases. This principle imposes inherent limitations on an eavesdropper’s ability to measure MUBs simultaneously with high precision, making it impossible for the eavesdropper to intercept or manipulate transmitted quantum information without being detected. Subsequently, the no-cloning theorem, as a second pillar, states that it is impossible to perfectly copy a quantum state, i.e., no quantum process can generate two identical copies of an unknown quantum state. Imagine a unique key that can open a lock, but this key cannot be duplicated. If the eavesdropper tries to intercept and copy the key, the attempt will fail or alter the original key, exposing the eavesdropper to the sender and receiver. Lastly, the superposition principle and quantum entanglement form the third pillar of unconditional security. The superposition principle enables information encoding in qubits, representing multiple classical bits simultaneously, making it difficult for eavesdroppers to intercept without detection, while quantum entanglement enables the secure distribution of encryption keys, ensuring that intercepted information remains confidential. This property is essential for various protocols, including QKD. Together, these principles provide unprecedented levels of protection against interception and decryption by eavesdroppers without detection, serving as a cornerstone in quantum cryptography by enabling the creation of unconditionally secure cryptographic keys.

Beyond these physical principles, unconditional security in QKD is rigorously established through mathematical proofs [24,25,26]. Over the past two decades, numerous unconditional security proofs have been developed for a wide range of QKD protocols [2, 13, 14, 27] and references therein, establishing a rich body of theoretical results that underpin the claim of unconditional security. For example, new approaches such as the use of mismatched basis measurements have provided simple and rigorous proof methods for the security of practical QKD in the single-qubit regime [28]. Nevertheless, practical realizations of QKD systems still face challenges due to device imperfections and side-channel loopholes. To mitigate the most critical detector vulnerabilities, measurement-device-independent QKD (MDI-QKD) was proposed [29, 30], which removes all detector-side channels by allowing the measurement process to be performed by an untrusted relay. This paradigm has since been extended to other secure communication tasks, such as MDI-QSDC [31,32,33] and MDI-QSS [34], thereby broadening the applicability of device-independent principles beyond key distribution. In parallel, an exciting subfield known as quantum hacking [35, 36] systematically studies and exploits implementation loopholes, further guiding the development of countermeasures such as MDI-QKD and MDI-QSDC to strengthen real-world security implementations.

2.1.1 QKD

QKD generates random secret keys shared between two remote parties, typically Alice and Bob. In 1984, the first QKD protocol was proposed, known as BB84 [1]. The basic security of the BB84 QKD protocol arises from the principles of quantum mechanics, with HUP playing a central role. In QKD security proofs, three types of attack strategies are typically analyzed: individual attacks, collective attacks, and general (coherent) attacks [2, 13, 14]. These are categorized as the weakest, moderate, and strongest attacks, respectively, corresponding to different levels of adversarial power constrained only by the laws of quantum mechanics. While general attacks are the most difficult to analyze, an important result shows that an eavesdropper cannot gain more information under general attacks compared to collective attacks [37]. Thus, proving security against collective attacks often implies unconditional security even against the most general attacks, for instance, the BB84 protocol’s security proof against collective attacks also covers coherent attacks [37]. Besides theoretical proposals, QKD technology has undergone extensive research and development on experimental grounds [14], reaching a high level of maturity. Moreover, much progress has been made in integrating QKD technology into current and future communication networks [2, 38].

2.1.2 QSDC

QKD aims to establish unconditionally secure keys. However, QC encompasses more than just secure key generation; it also involves the timely transmission of secret messages. QSDC is one such application beyond QKD that directly transmits secret information over a quantum channel, without the need for prior secret key distribution. Since its introduction in 2000, QSDC has rapidly developed into a perfectly secure application. QSDC is a one-way protocol, with information flowing from A to B (the nearest classical analogue is simplex). However, QD is another interesting aspect of secure direct communication, using a two-way communication where information flows both ways, i.e., A to B and B to A simultaneously (the nearest classical analogue is duplex). Both QSDC and QD fall under direct secure QC, allowing the transmission of secret messages directly without the need for prior quantum key generation. QD is relevant, particularly in scenarios requiring bidirectional QC. The scientific community is exploring QSDC’s benefits for QC networks, aiming to build a quantum internet [39] using secure repeater networks (SRN) and QSDC to transmit ciphertext encrypted by quantum-resistant algorithms [9] of [39]. This hybrid quantum network offers secure end-to-end communication without relying on trusted-repeater nodes. Implementing QSDC is challenging because of the need for higher qubit rates and reliable quantum memory. Current quantum memory prototypes lack the necessary duration and robustness for practical applications. However, quantum-memory-free QSDC proposals offer a potential solution to these challenges [39].

Interestingly, QSDC has been experimentally realized for free-space links [39] and aspires to be an integrable technology with 6G communication systems. A 2021 white paper [40] by world-leading communication experts highlighted QSDC’s potential in 6G. Recently, LG Electronics achieved higher transmission rates (1.6 Mbps at 10 Km) using high-dimensional states compared to the original DL04 QSDC (50 bps at 1.5 Km). With advances in quantum memory and low-loss fibers, QSDC could become a major form of QC in the near future.

2.1.3 Semi-QC

Unlike fully QC protocols [2] like QKD, QSDC, and QD, semi-quantum protocols [41, 42] aim for unconditional security with fewer quantum devices, allowing some participants to use classical devices. This approach is cost-efficient and resource-saving, as quantum resources are expensive and fragile in noisy environments.

Interestingly, semi-quantum communication criteria can be considered one of the realistic parameters that can be used to assist in the design and benchmark the performance of future missions in building the quantum network in satellite-based applications or even connecting the quantum cities globally [43]. Further, in a satellite-based communication system, the semi-quantum device (regime) can be an emergency replacement [41, 42] when a quantum device ever fails or breaks down at the ground station, which helps the satellite to continue secure communication (to work) until the quantum device repairs, thereby providing an efficient and cost-saving option during the operation time of the satellite. It is therefore potentially beneficial and practical to explore such semi-quantum versions of satellite-based QKD/other quantum applications.

2.2 Multiparty quantum computation protocols

A quantum internet comprises a network of interconnected quantum processors linked by QC channels, facilitating computation by transferring inputs/outputs. Besides unconditional security, QC networks enhance in-network distributed computing power and reduce overall end-to-end latency beyond intrinsic classical technology limits [44]. Some important secure multiparty quantum computation (SMQC) protocols are quantum voting, BQC, and others that achieve security if the majority of participants are honest. Some of these SMQC tasks include the anonymity feature, one of the most stringent requirements against a powerful quantum adversary. Some of the quantum anonymous protocols can be used as sub-protocols to fulfill anonymity requirements, i.e., hiding the identity of the sender or the receiver or both, message transmission, and entanglement generation in several SMQC networks. The anonymity feature (dual to authenticity in specific networks) can be visualized in the following applications.

2.2.1 Quantum voting and veto

To execute collective decisions in a democratic country, voting is one of the top-priority cryptographic primitives in SMQC. For the development of the secure electronic voting system, the anonymous feature plays a crucial role in quantum voting protocols, where users do not want their votes to be disclosed during the public announcement of the outcome of the voting. An anonymous voting protocol has been proposed using a quantum-assisted blockchain where the link between the voter and the vote is hidden. Similarly, quantum veto protocols are one of the subclasses of quantum voting protocols, rejecting a proposal completely if even one (or more) of the voters rejects it to vote among several voters. The anonymity of such a voter is paramount for quantum anonymous veto (QAV) protocols. Recently, researchers experimentally tested the QAV protocol of four voters on the IBM quantum computer.

2.2.2 BQC

Blindness and correctness are the characteristics of BQC to ensure the client’s privacy and security issues (against the quantum server) of quantum computation protocols. It is an effective and secure method where quantum servers with universal quantum computers can perform the quantum computational tasks delegated by the clients equipped with poor quantum technology, in such a way that the security theory of BQC protocols guarantees its characteristics of the input, computational algorithm, and output of the clients. Further, BQCs are classified as single-server, double-server, triple-server, etc. BQC offers practical benefits for 6G, enabling task offloading and blind computation, keeping the cloud unaware of the computation performed. BQC can harness the powers of federated quantum machine learning that collaboratively trains a model while ensuring data remains decentralized across multiple remote quantum nodes. Another application is secure multiparty quantum private information query protocols, using universal BQC, ensuring privacy and security in quantum cloud computing. BQC guarantees blindness and correctness, so clients only receive information relevant to their queries, and servers cannot access client queries.

3 Role of NTNs in QC

The vision for 6G infrastructure includes a global-scale network supported by quantum applications, which necessitates the global coverage provided by NTNs. NTNs [38] aim to offer extensive coverage over long distances, enhancing communication connectivity for end users in unserved and underserved areas. In fact, realizing such a global-scale network in the quantum regime involves integrating quantum networks into space, ground, and underwater communication infrastructure. For instance, a hybrid communication sequence from Satellite-Air-High Altitude Platforms (HAPs)-Balloons-Drones-Ground-Sea would provide a huge communication infrastructure spanning space, air, ground, and underwater. By harnessing entanglement swapping, each NTN element, including satellites, HAPs, balloons, and drones, can serve as quantum repeaters for quantum teleportation. These elements are pivotal in establishing trusted-repeater-based satellite QKD networks, HAPs QKD networks, balloon QKD networks, drone QKD networks, or their combinations, forming a sophisticated global space-based QC infrastructure. Additionally, the architecture of double-layer quantum satellite networks [45] provides a valuable framework for hierarchical network arrangements, catering to diverse network requirements.

The role of NTNs, coupled with quantum resources [46], facilitates the realization of quantum cities [2, 43] globally, ensuring the unconditional security provided by quantum mechanics. While terrestrial networks (TNs) have traditionally been the focus of QC security, recent research has explored NTNs extensively since the successful launch of the Chinese Micius satellite [47]. Researchers are increasingly integrating NTNs with TNs to establish an NTNs-TNs (hybrid) infrastructure [38], for secure long-range quantum network applications. Beyond the pioneering demonstrations such as the Micius satellite [47] and drone-based QC experiments [48], a number of other application-oriented schemes for quantum network construction have emerged. Terrestrial fiber-based quantum networks, such as metropolitan and backbone deployments, provide a practical path toward secure QC integrated with existing telecom infrastructure. For instance, hybrid trusted/untrusted relay-based architectures over optical backbone networks have been proposed to combine the scalability of trusted-node schemes with the enhanced security of measurement-device-independent and entanglement-based protocols [49]. At a broader scale, satellite-assisted multi-node scenarios have been investigated through simulations, showing how quantum-secured links between cities can be achieved by constellations of satellites beyond a single platform demonstration [43]. More recently, the vision of space–air–ground integrated networks has been put forward, offering a unified framework to interconnect fiber backbones, drone relays, and satellites for seamless and global quantum-secured communication [38]. Together, these approaches illustrate that the roadmap toward a quantum internet is not limited to satellites or drones alone but involves hybrid and heterogeneous architectures that balance practicality, scalability, and security. However, realizing hybrid NTNs–TNs infrastructures for 6G quantum networks faces several challenges. Free-space quantum channels suffer from high channel loss, decoherence, and atmospheric turbulence [50, 51]. Maintaining stable links with fast-moving aerial or maritime nodes requires advanced acquisition, tracking, and pointing systems [52]. Environmental factors such as atmospheric and sea-surface turbulence including absorption, scattering, and refractive distortions over maritime links further limit the reliability [53, 54]. Additionally, hybrid NTNs–TNs systems demand precise synchronization and resource management across heterogeneous platforms, complicated by Doppler shifts and propagation delays [55]. Moreover, scalable deployment will depend on advances in quantum repeaters and long-lived quantum memories, which remain experimentally challenging [56, 57]. Finally, seamless integration with classical 6G infrastructure requires cross-layer design and optimization frameworks that remain at an early stage [58].

In NTN settings, while QKD has played a crucial role and has been explored more seriously in the field of satellite-based QC [2], later, other quantum applications have been applied to find solutions by solving potential problems. QSDC is one such application, whose key aspects have been discussed in 2.1.2. Moreover, about both fiber-based and free-space-based QSDC implementation, recently, researchers have proposed the idea of combining QSDC with an SRN to overcome the limitations of quantum networks (directly connected nodes or nodes connected to a common node) and to enable an information-theoretically secure solution using a quantum-resistant algorithm [39]. They demonstrated the first such hybrid quantum network experimentally operated in sequence through an optical fiber and a free-space communication link. Additionally, this technology shows promise for satellite-based applications, considering SRN an implementable technology. Even further, the researchers performed a study of the atmospheric turbulence of an orbital-angular-momentum-based QSDC (see [78-79] of [59]). Furthermore, in [59], the theoretical and experimental perspectives of free-space QSDC have been discussed along with fiber and free-space hybrid optical networks. Some specific issues in free-space and satellite-to-ground QSDC are explained in detail. The possible characteristics of novel free-space QSDC protocols are provided, suggesting one-way QSDC are the best candidates for an excellent QSDC system with low hardware complexity and high secrecy capacity. This assertion is further supported by a recent experimental demonstration of the STIKE one-way quasi-QSDC protocol: the system operated at a repetition rate of 1.25 GHz over a communication distance of 104.8 km in a standard telecommunication fiber [8]. Such a demonstration indicates the practicality of long-distance quasi-QSDC and therefore helps pave the way toward building space–air–ground–sea integrated secure communication networks using quantum states. The feasibility of such satellite-based QC applications addresses the distance limitations of fiber-based quantum networks, paving the way for quantum-enabled 6G infrastructure with unconditional security.

4 Role of QC in 6G

QC emerges as a promising enabling technology for envisioning a quantum-enabled 6G infrastructure. However, current quantum algorithms and future quantum attacks can compromise the security of 6G networks. Consequently, ensuring robust network security is paramount in 6G communication, necessitating the implementation of well-integrated security mechanisms. A potential enabling technology is QKD which can secure the backhaul of 6G network as well as secure the communication of data center.

Table 1 6G-enabled application domains and their respective specific key quantum feature (KQF) requirement. A “Yes” indicates the relevance of a specific KQF for the application domain, while a “No” denotes that the particular KQF is not significant for that domain

| KQFs | S | A | \(E_C\) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Application domain | |||

| e-Healthcare | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Finance and banking | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Telecommunications and Internet-of-Everything | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Transportation | Yes | No | Yes |

| Smart cities and industry | Yes | Yes | No |

| Satellite network applications | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Defense and military | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Thus, achieving unconditional security (S), anonymity (A), and communication efficiency \((E_C)\) through SDC stands out as key quantum features (KQFs) as outlined in Table 1. At the same time, it is essential to identify quantum applications compatible with the upcoming 6G technology, facilitating seamless integration [21, 40]. Table 1 outlines QC features that can enhance several critical application areas, demonstrating the feasibility of integrating quantum technologies into future 6G networks. The application areas mentioned in column I of Table 1 are justified for the QC adoption despite its high costs, due to the unconditional security, efficiency, and resilience it offers. Current classical solutions (algorithms like Rivest Shamir Adleman, data encryption standard, Diffie-Hellman, and elliptical curve cryptography) fall short in protecting against quantum threats (algorithms like Shor, Grover, and hybrid), making QC essential for high-stakes sectors like finance, banking, defense, and national security. This necessitates incorporating QC into the existing classical infrastructure, a crucial step toward realizing 6G quantum technology.

Mentioned below are the key areas where quantum technologies could be applied to 6G networks, viz., (i) in the development of quantum sensors, capable of detecting and measuring a variety of physical parameters, such as temperature, pressure, and magnetic fields, with such high precision that not only do they (quantum sensors) outperform but also impossible with classical sensors. This can have applications in specific 6G fields, e.g., integrated sensing and communication, which holds significant potential in military communications and weather forecasting. (ii) Quantum computing could be applied to 6G networks to optimize (the operation) network performance such as task offloading in mobile edge cloud and open radio access networks, which hold potential applications in telecommunications and internet of things, finance, banking, transportation, and even in medicine and drug discovery, and also by using quantum algorithms to analyze large data sets develop new, efficient, secure communication protocols, which hold significant potential in the e-healthcare and e-commerce sectors. (iii) Further, the development of QC networks is one of the most prominent key areas that could be applied to enhance the security of several sectors such as defense and military, banking and finance, e-healthcare, and satellite network applications. QKD stands as a pivotal quantum application and enhances 6G network security. Besides QKD, QSDC, once fully developed, offers the potential for secure next-generation communications [40], when integrated into current classical architectures.

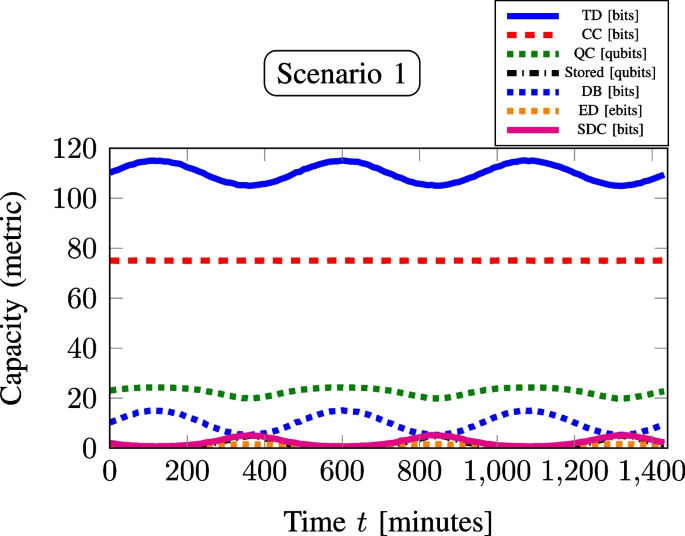

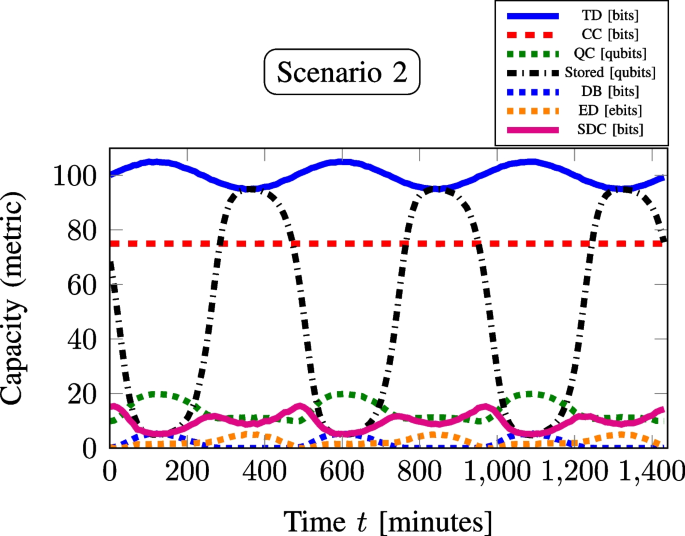

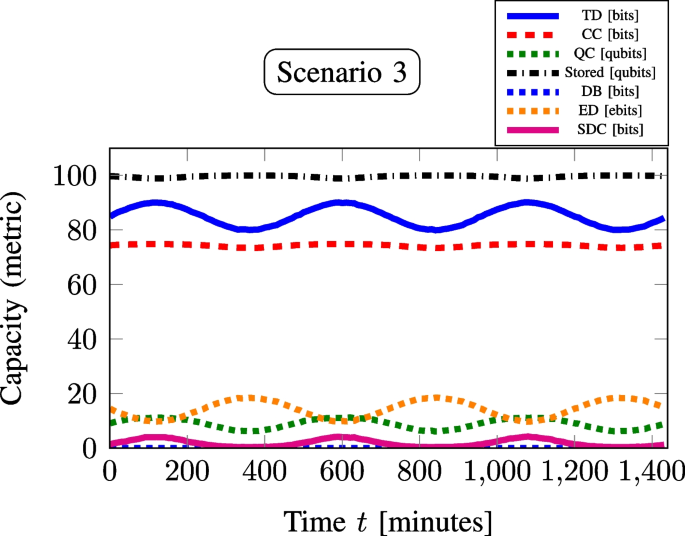

Table 2 The table, derived from Figs. 2, 3, 4, and 5 for S1–S4 simulations, summarizes metric capacities across all four scenarios, highlighting SDC’s full quantum advantage at high TDs, with S2’s DTD(95) (troughs) performing best

| S | MTD | DTD | C | Q | Stored qubits (QM) | ED (Bell pairs) | SDC | DB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 110 | 115 (peaks) | 75 | 24 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 14 |

| 105 (troughs) | 75 | 21 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 5 | ||

| S2 | 100 | 105 (peaks) | 75 | 21 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 5 |

| 95 (troughs) | 75 | 10 | 95 | 5 | 10 | 0 | ||

| S3 | 85 | 90 (peaks) | 75 | 11 | 97 | 9 | 4 | 0 |

| 80 (troughs) | 73 | 7 | 100 | 18 | 0 | 0 | ||

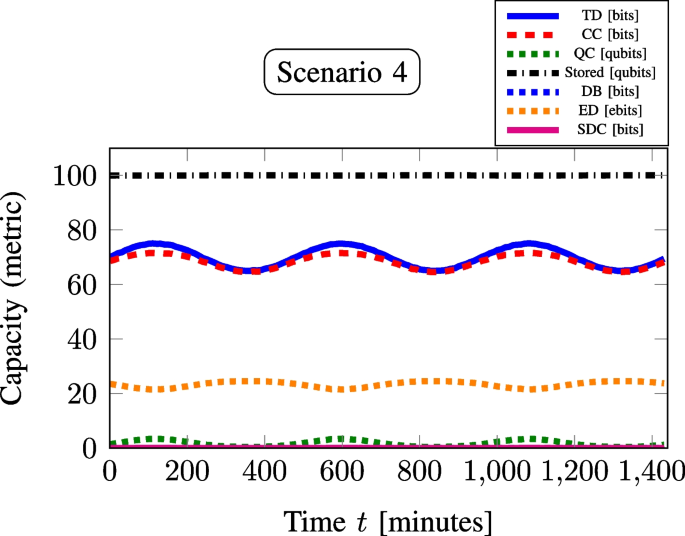

| S4 | 70 | 75 (peaks) | 72 | 3 | 100 | 22 | 0 | 0 |

| 65 (troughs) | 64 | 1 | 100 | 24 | 0 | 0 |

Further, QC protocols play a significant role in enhancing the communication rate in 6G-based quantum networking protocols. Specifically, SDC [60] can transmit large amounts of data by doubling the data transmission rate, thereby reducing congestion on 6G communication networks. SDC is a QC protocol that enables Alice to transmit 2 classical bits (00, 01, 10, 11) to Bob sending just 1 qubit, leveraging their pre-shared entanglement. Alice and Bob each have 1 qubit. Alice encodes her message by applying a specific quantum operation (I, X, Y, Z) to her qubit and then sends it to Bob. Bob decodes the message by performing a joint measurement on both qubits. This protocol effectively doubles the classical information that can be sent with a single qubit, demonstrating a key advantage of QC. While SDC primarily demonstrates throughput enhancement, QC protocols also provide unique advantages of eavesdropping detection and information-theoretic security. Such properties are crucial in application scenarios where undetected interception cannot be tolerated. Examples include 6G control-plane signaling and network slicing [61], non-terrestrial networks (satellite and inter-satellite links) [47, 50], critical infrastructure systems such as smart grids and defense networks [62], and highly sensitive domains like financial transactions and healthcare data exchange [23, 63]. Thus, SDC’s capacity advantage and quantum communication’s intrinsic security complement each other in future 6G architectures [23].

5 System model and simulation results

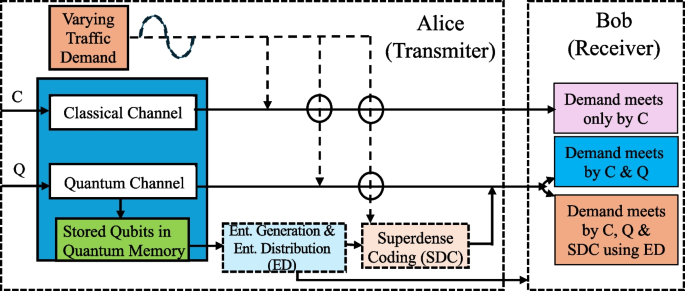

In Fig. 1, we illustrate a system model involving two communicating parties, Alice (transmitter) and Bob (receiver), within which the network protocol operates. The network protocol analysis aims to optimize resource usage by first maximizing the use of classical bits to handle the varying TDs. Once the capacity of classical bits is exhausted, the protocol utilizes qubits to meet additional demand. If traffic still exceeds available resources, the network uses the entanglement generated (from stored qubits) to exploit SDC, thus maximizing data transmission efficiency. The qubits for entanglement generation are derived from qubits that were not utilized by the network in previous cycles when the TDs were low and could be sufficiently met by classical bits alone. These qubits are stored in quantum memory, allowing the network to leverage them whenever needed to generate entanglement to facilitate ED for future QC applications; SDC immediately using ED, during high TDs; or both ED and SDC, simultaneously.

As described above, Alice optimizes network resource usage and executes the data communication to Bob in three efficient ways (see Fig. 1) under varying TDs across four scenarios (S): S1, S2, S3, and S4, respectively. These scenarios are simulated via Python programming using numpy and matplotlib libraries and analyzed and plotted in Figs. 2, 3, 4, and 5, respectively. In our simulations, the traffic arrival process, i.e., TD, is modeled as a Poisson process. The mean traffic demand (MTD) for each scenario is given as 110, 100, 85, and 70 bits/min (corresponding to S1, S2, S3, and S4), with an additional sinusoidal variation of amplitude 5 bits/min to represent dynamic traffic demand (DTD). Formally, the time-dependent mean arrival rate is defined as follows:

where MTD is the scenario-dependent mean traffic rate, A is the sinusoidal amplitude (5 bits/min in our case), k is the number of sinusoidal cycles within the observation window T, and t represents time (minutes). The probability of mean arrival rate \(\lambda (t)\) to be Poissonian was implemented by using random.poisson Python function in our simulation.

The network protocol considered a classical channel capacity (C) of 75 bits/min, a quantum channel capacity (Q) of 25 qubits/min, and a quantum memory (QM) capacity of 100 qubits/min starting with 0 qubits stored. As the network runs, unused qubits accumulate in QM. Alice utilizes these stored qubits for entanglement generation (2-qubits) of Bell pairs (ebits) to efficiently communicate with Bob, enabling (i) ED for future QC applications, (ii) SDC immediately using ED, during periods of high TDs, or (iii) both ED and SDC, simultaneously. Each Bell pair in ED doubles the transmission rate through SDC. Further, the dropped bits (DB) are lost bits that the communication channel cannot recover, and the goal is to prevent dropping bits while efficiently optimizing network resource usage.

To highlight the quantum advantage of SDC during high TDs, we simulated traffic data for 24 h using a Poissonian distribution. The total communication rate (y-axis) versus time (minutes) of the day (x-axis) is plotted for scenarios S1, S2, S3, and S4, as shown in Figs. 2, 3, 4, and 5, respectively. Although the mean traffic rate follows a smooth diurnal sinusoidal variation, the actual traffic arrivals are generated via the Poisson process, thereby incorporating natural random variability into the demand. The Poisson model is a well-established approach in traffic engineering for representing uncorrelated random arrivals [64, 65], and it has been widely used in both telecommunication and computer network studies. This distinction between the deterministic mean rate and the stochastic arrivals is crucial, since it ensures that the simulation curves (Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5) reflect realistic conditions rather than purely deterministic trends. The analysis of these plots for various communication metrics, as detailed in Table 2, provides a summary of the results for the four scenarios. It highlights their respective MTD values and the corresponding DTD values, represented by the observed peaks and troughs as shown in Figs. 2, 3, 4, and 5. The simulations in this work were performed assuming an ideal QC channel, i.e., without considering channel noise or entanglement degradation, to clearly demonstrate the proof-of-concept advantage of SDC in scenarios with high TDs. However, for practical implementation of such a resource-efficient system model (Fig. 1) in 6G quantum networks under varying traffic loads, it would be essential to incorporate an entanglement purification [66] after the entanglement distribution stage to maintain high-fidelity entanglement. This is critical for ensuring efficient execution of SDC and other QC applications in realistic noisy channels [66, 67]. The one-step QSDC protocol based on entanglement, as reported in [68], offers a promising approach to address the limitations arising from imperfect entanglement and channel noise, thereby strengthening the feasibility of the proposed framework.

We provide a brief explanation of the simulations for each scenario, highlighting their significance below:

S1 exhibits the highest MTD(110), with a DTD of 115 (peaks) (105 (troughs)). The network uses resources C(75), Q(24) (C(75), Q(21)), with QM storing 2 (4) qubits to generate 1 (2) Bell pair(s) for ED(1) (ED(2)), transmitting 2 (4) bits taking advantage of SDC(2) (SDC(4)). However, these scenarios experience a DB of 14 (5), resulting in TD bit loss, which is unfavorable for the network.

S2 shows the second-highest MTD(100), with DTD(105) (peaks), explains similar to S1’s troughs at 105. However, S2 with DTD(95) (troughs), the network utilizes resources C(75) and Q(10), while 95 single qubits are stored in QM, of which the network uses 10 qubits to generate 2-qubit entanglement to produce 5 Bell pairs for entanglement distribution (ED (5)). Using the SDC protocol, each Bell pair can transmit 2 bits of classical communication by sending just 1 qubit. Thus, 5 Bell pairs transmit 10 bits of classical communication, requiring only 5 qubits. Without SDC, 10 qubits would be needed to transmit the same 10 bits. This example demonstrates how SDC doubles the classical data transmission per qubit, effectively meeting high TD without dropping any bits.

S3 shows the second-lowest MTD(85), with DTD(90) (peaks), and after utilizing C(75), Q(11), the network uses 18 qubits (from 97 qubits stored in QM) to generate total 9 Bell pairs for (ED(9)), of which 2 Bell pairs can be used for SDC(4) to fulfill DTD(90) and the rest of 7 Bell pairs can be distributed for future QC applications. This scenario is suitable for both SDC and ED without DB(0). However, S3 with DTD(80) (troughs), the network uses resources C(73), Q(7) to meet DTD(80). Further, the network uses 36 qubits (from 100 qubits stored in QM) to generate 18 Bell pairs for (ED(18)); all can be used (suitable scenario) to prepare the network for future QC applications, without DB(0).

S4 illustrates the lowest MTD(70), with a DTD(75) (peaks) (65 (troughs)), fulfilled by the network resources C(72), Q(3) (C(64), Q(1)) without DB(0). The simulation shows that the network uses 44 (48) qubits (from 100 qubits stored in QM) to generate 22 (24) Bell pairs for ED(22) (ED(24)). These scenarios are favorable for reserving distributed entanglement, facilitating future QC applications between Alice and Bob.

6 Conclusion

Quantum information harnesses quantum resources to facilitate both QC and computational tasks, which find diverse practical applications. While procuring unconditional security, QC protocols offer unique communication and computational features by leveraging quantum advantages. QC is an emerging technology expected to play a pivotal role in building global-scale secure quantum networks through NTNs, with significant implications for future 6G network capabilities.

In this article, we discussed the QC and computation protocols along with their key features. We explored the role of NTNs in QC, particularly highlighting the potential of satellite-based QSDC networks that enable secure and efficient communication over large distances. Subsequently, we analyzed the role of QC in 6G technology, identifying potential application areas where 6G-enabled quantum systems can enhance network performance by utilizing the KQFs. The key innovation of our work lies in proposing a system-level simulation framework to evaluate the integration of QC into 6G networks. Through four traffic demand scenarios, our numerical simulations demonstrated how SDC can significantly enhance transmission efficiency by doubling data rates under high traffic conditions, while enabling entanglement resources to be preserved under lower demands for future applications. This highlights the adaptive potential of QC protocols in optimizing resource utilization across diverse network conditions. Thus, for future 6G networks with entanglement sharing, storage, and manipulation capabilities, SDC will become a practical and desirable functionality. Moreover, incorporating machine learning (ML) into SDC represents a promising direction, enabling networks to detect inefficiencies and dynamically trigger SDC when most beneficial. With unparalleled security, extended global reach, and enhanced data transmission speeds, the integration of quantum technologies with 6G networks has the potential to revolutionize communication infrastructure and meet the evolving needs of modern society.