1 Introduction

The development of modern quantum computers presents new opportunities for solving high-intensity computational problems, including the electronic structure problem which is fundamental to quantum chemistry [1, 2]. Quantum devices remain in the noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) era, characterized by a limited number of qubits and high levels of noise [3, 4]. Furthermore, electronic structure calculation remains computationally challenging due to electron correlation effects [5]. Current state-of-the-art classical methods such as Hartree–Fock (HF) [6] and density functional theory (DFT) [7, 8] still encounter difficulties in accurately capturing electron correlation, particularly in many-electron systems [9, 10]. These constraints have motivated hybrid quantum–classical algorithms [11,12,13], notably the variational quantum eigensolver (VQE) [14,15,16,17], which are more resilient to qubit limitations and noise compared to purely quantum algorithms. VQE-based methods have demonstrated effectiveness in handling electronic structure problems for small molecular systems by combining classical optimization with quantum computing to prepare and measure wavefunctions. However, further development is necessary to extend these methods to systems with more electrons, large basis sets, and increased molecular complexity.

A crude but common strategy to fit within NISQ hardware is to work in a minimal basis set [18,19,20]. Reducing the number of spin orbitals cuts qubits and circuit depth, but sacrifices diffuse and polarization functions that are essential for high-quality correlation energies. To achieve higher precision, larger basis sets must be utilized. Expanding the basis set increases the number of required qubits, as each additional orbital enlarges the Hilbert space that needs to be explored. Furthermore, a larger basis set also leads to greater circuit depth [21], since more quantum gates are necessary to prepare and measure the system’s state. This, in turn, amplifies error accumulation and noise, further complicating the computations [22,23,24,25]. Error mitigation [26,27,28,29,30,31,32] and qubit tapering [33] alleviate part of the overhead, but the number of logical qubits still scales with the size of the active orbital space.

One way to address the challenges posed by larger basis sets and limited qubits is to optimize the selection of orbitals, commonly referred to as orbital optimization [34,35,36,37,38]. This strategy aims to retain the accuracy benefits of a more expansive basis set while mitigating the computational overhead described earlier. Previous work, such as OptOrbVQE [38], demonstrated that focusing on orbitals with the lowest HF energies can achieve high accuracy under strict qubit constraints by using a partial unitary matrix to select those orbitals. Nevertheless, the critical question remains whether systematic orbital selection is essential or if randomness can provide similar advantages with reduced computational overhead. Building on this notion, we propose random optimal orbital variational quantum eigensolver (RO-VQE), a modified algorithm derived from OptOrbVQE that employs a randomized procedure for selecting and optimizing orbitals. While OptOrbVQE is based on molecular orbitals (MO) selection via HF energies, RO-VQE explores whether randomized orbital selection can achieve comparable accuracy, offering a more flexible and potentially hardware-efficient alternative. Should such strategies prove equally effective, it would imply that the choice of active space is less critical than previously assumed. Conversely, if MO-based selection significantly outperforms random selection, the importance of targeted orbital optimization in the VQE would be reaffirmed, especially as we strive to tackle larger systems within the limitations of current quantum hardware.

In this work, we apply RO-VQE for hydrogen chain systems, a controllable testbed for strong correlation [39,40,41]. For the H4 molecule, we employ a larger 6-31G split-valence basis set to investigate whether expanding beyond minimal basis sets influences the relative performance of MO-based versus random selection strategy. Meanwhile, for the H2 molecule, we keep the number of spin orbitals constant at four, the same as in a minimal basis set, but vary the basis sets themselves to assess whether changing the underlying orbitals affects the algorithm’s robustness. These controlled experiments establish performance baselines that will guide future NISQ implementations.

The remainder of this work is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the theoretical background, including an overview of the VQE and the specific details of RO-VQE. Section 3 describes our simulation results and discussion, beginning with an exploration of different spin-orbital counts and proceeding to an examination of how variations in the basis set influence performance. Finally, Sect. 4 concludes the paper by summarizing the key findings and outlines avenues for further research. The code for this study is available on https://github.com/Yogaag99/ROOVQE.

2 Theory

2.1 Variational quantum eigensolver

Variational principle states that the ground state of a system E0 could be approximated by the energy \({E}_{\Psi \left(\theta \right)}\) calculated from the expectation value of Hamiltonian \(\widehat{H}\) with respect to the varied wavefunction \(|\Psi (\theta )\rangle\) [42]

where \(|\Psi (\theta )\rangle\) is generated by applying a parametrized ansatz circuit \(\widehat{U}(\theta )\) to the reference state \(|{\Psi }_{\text{ref}}\rangle\). The resulting state is

The electronic structure Hamiltonian \(\widehat{H}\) could be formulated in the second quantization as

where

are the one- and two-body integrals, respectively, over the set of \(M\) basis functions \(\{{\psi }_{1}, {\psi }_{2},\dots ,{\psi }_{M}\)}.

The VQE algorithm tries to find a value of θ parameter that yield the minimum energy \({E}_{\text{min}}\). Thus, this search problem could be written as a minimization problem,

This fermionic Hamiltonian can be mapped to a qubit Hamiltonian using the Jordan-Wigner transformation [43, 44]. While alternative mappings exist (e.g., Parity [45] or Bravyi-Kitaev [46,47,48]), we employ Jordan-Wigner for its straightforward implementation and compatibility with our orbital optimization framework. The resulting qubit Hamiltonian consists of tensor products of Pauli operators \({P}_{k}={\otimes }_{j}^{N}{\sigma }_{k,j}\) where \({\sigma }_{k,j}\in \{{\mathbb{I}}, {\sigma }_{x}, {\sigma }_{y}, {\sigma }_{z}\}\)

A quantum computer prepares the wave function and effectively measures the expectation value \(\left.\langle \Psi \left(\theta \right)\right|{P}_{k} |\Psi (\theta )\rangle\) by executing the quantum circuit with \(\widehat{U}(\theta )\) for each \({P}_{k}\), followed by rotations \({R}_{k}\in \left\{{\mathbb{I}}, {R}_{x}\left(-\frac{\pi }{2}\right), {R}_{y}\left(\frac{\pi }{2}\right)\right\}\) depending on \({P}_{k}\), before measuring qubits in the \(z\)-basis. The classical computer then computes the weighted sum of these expectation values. Using a classical optimization algorithm, such as gradient-based methods [49,50,51,52,53,54], the parameters \(\theta\) are updated iteratively to minimize \({E}_{\Psi \left(\theta \right)}\). The optimization process iterates until the convergence criteria are met, yielding the parameter set \({\theta }_{\text{min}}\), which approximates the ground state \(|\Psi ({\theta }_{\text{min}})\rangle\) of the Hamiltonian \(\widehat{H}\). The corresponding minimum energy is

2.2 Random orbital optimization VQE

In the VQE framework, orbital optimization serves as an effective strategy to reduce qubit requirements while preserving computational accuracy. This approach is inspired by the OptOrbVQE algorithm, previously introduced in MO-based orbitals selection. Conventionally, a basis set of \(M\) spin orbitals requires \(M\) qubits for simulation if no reduction techniques are applied. However, practical quantum hardware constraints often limit the available number of qubits to \(N\) qubits where \(N

To address this, the Hamiltonian is projected onto a subspace containing only \(N\) spin orbitals using a partial unitary transformation, represented by an \(M\times N\) real matrix \(\widehat{V}\). This transformation modifies the basis functions as:

The transformed Hamiltonian, expressed as a function of \(\widehat{V}\), is given by:

The one- and two-body integrals in the transformed basis are:

where the primed indices \((p{\prime}, q{\prime}, r{\prime}, s{\prime})\) correspond to the transformed basis functions, while the unprimed indices \((p, q, r, s)\) represent the original basis functions. For instance, \(\widehat a_p^{\dagger}\) is the fermionic creation operator for the original spin-orbital \({\psi }_{p}\), whereas \(\widehat a_{p}^{\dagger}\) corresponds to the transformed spin-orbital \({\widetilde{\psi }}_{{p}{\prime}}\).

Once transformed, the fermionic Hamiltonian is mapped to a weighted sum of Pauli operators for quantum computation, ensuring flexibility in the choice of encoding scheme. The expectation values:

correspond to the one- and two-particle reduced density matrix (1-RDM and 2-RDM) elements, denoted as:

These quantities are measured on a quantum computer after mapping to qubit operators, using the ansatz state:

This measurement process follows the same methodology as in conventional VQE but benefits from the reduced qubit requirements and optimized orbital representation provided by the transformation. The ground-state energy depends on both the ansatz parameters \(\theta\) and the partial unitary matrix \(\widehat{V}\). Consequently, the ground state search problem is formulated as a joint minimization over the space of variational parameters and the space of all real partial unitary matrices of size M × N:

where the constraint on \(\widehat{V}\) is given by:

This optimization problem involves two distinct parameter sets, each governed by different constraints:

-

The partial unitary matrix \(\widehat{V}\), which satisfies an orthogonality condition ensuring that its columns form an orthonormal basis.

-

The variational parameter vector \(\theta\), which typically consists of real numbers subject to predefined bounds.

To efficiently solve this optimization problem, we adopt a strategy inspired by the OptOrbVQE approach in the MO-based setting. The minimization is divided into two sequential subproblems:

-

Optimization over \(\widehat{V}\): The energy is minimized with respect to the partial unitary matrix \(\widehat{V}\) while keeping θ fixed.

-

Optimization over \(\theta\): The ansatz parameters \(\theta\) are optimized while holding \(\widehat{V}\) constant.

The two interdependent minimization subproblems are iteratively solved until a predefined stopping criterion is met. To clarify the notation, the following iteration indices are used:

-

l: Iteration number for the optimization of \(\hat{V}\).

-

m: Iteration number for optimizing \(\theta\), analogous to standard VQE iterations.

-

n: Outer loop iteration count, indicating the number of times \(\hat{V}\) has been updated.

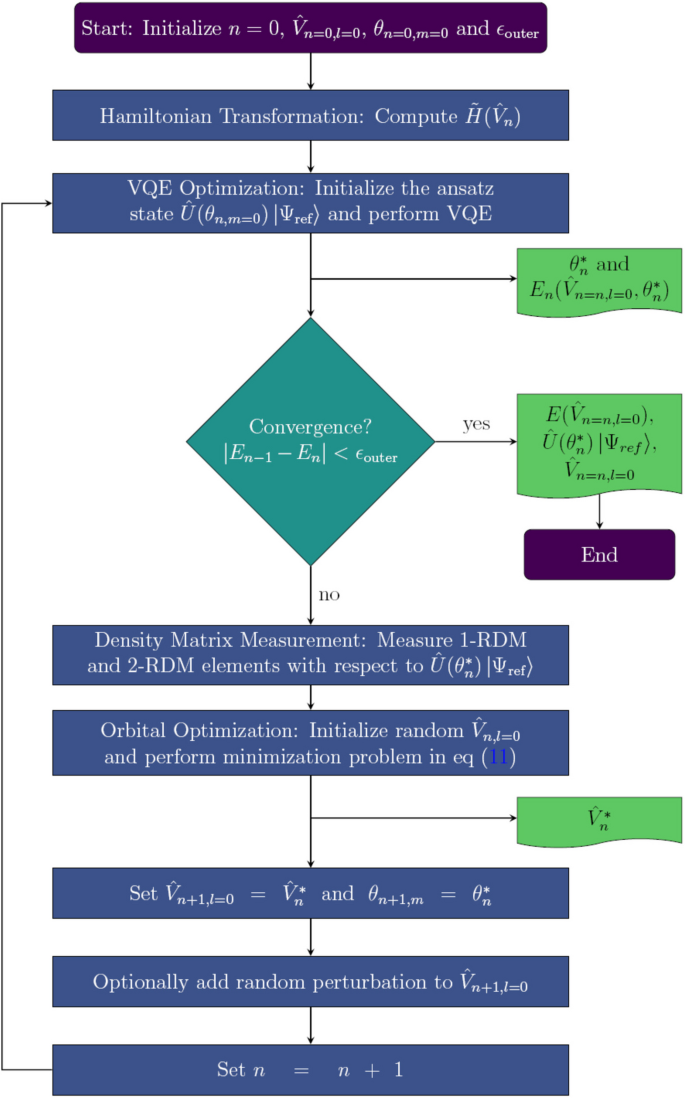

The optimal parameters for each subproblem at a given iteration are denoted with the asterisk ( ∗). The RO-VQE procedure follows the steps in Fig. 1, the explanation of which is written below:

- Start: Set the outer loop iteration count \(n=0\), initialize the unitary transformation \({\hat{V}}_{n=0,l=0}\) and VQE parameters \({\theta }_{n=0,m=0}\), and define a convergence threshold \({\epsilon }_{\text{outer}}\).

- Hamiltonian transformation: Compute the transformed Hamiltonian \(\tilde{H}({\hat{V}}_{n})\) on a classical computer and generate the corresponding qubit Hamiltonian.

- VQE optimization: Prepare the ansatz \(U ({\theta }_{n,m=0})|{\Psi }_{\text{ref}}\rangle\) and perform VQE to obtain the optimized variational parameters \({\theta }_{n}^{*}\) and the estimated ground-state energy \(E\left({\hat{V}}_{n,l=0},{\theta }_{n}^{*}\right)\).

- Convergence check: If the change in energy between consecutive iterations is below \({\epsilon }_{\text{outer}}\), terminate the process and return the optimized quantities \(E({\hat{V}}_{n,l=0}, U ({\theta }_{n}^{*})|{\Psi }_{\text{ref}}\rangle\), and \({\hat{V}}_{n,l=0}\). Otherwise, proceed to the next step.

- Density matrix measurement: Measure the one- and two-body reduced density matrices (1-RDM and 2-RDM) using the quantum computer with respect to the optimized ansatz state.

- Orbital optimization: Perform the optimization of \(\hat{V}\) using the obtained density matrices to minimize the energy further, resulting in the updated transformation matrix \({\hat{V}}_{n}^{*}\).

- Parameter update: Update the parameters for the next iteration, setting \({\hat{V}}_{n+1,l=0}={\hat{V}}_{n}^{*}\) and \({\theta }_{n+1,m=0}={\theta }_{n}^{*}\). To prevent convergence to shallow local minima, a small random perturbation may be introduced to \({\hat{V}}_{n+1,l=0}\).

- Iteration loop: Increment \(n\) and repeat VQE optimization to parameter update steps until convergence is achieved.

The initialization of the partial unitary matrix \(\widehat{V}\) of size \(M\times N\) can be constructed by orthonormalizing a randomly generated matrix. Given a real matrix \(A\in {\mathbb{R}}^{M\times N}\), the orthonormalization function is defined as:

where \(Q\) and \(\Lambda\) are obtained from the diagonalization of the Gram matrix [55]:

This ensures that the resulting matrix orth(A) satisfies the unitary constraint \({\widehat{V}}^{T}\widehat{V}={I}_{N}\), making it a valid transformation matrix for orbital optimization.

For practical implementation, the initial partial unitary matrix \({\widehat{V}}_{n=0,l=0}\) is chosen such that its elements are sampled from a selected random distribution. To enhance exploration and avoid convergence to shallow local minima, the updated partial unitary matrix at step 7 of the optimization process is defined as:

where \(\text{Rand}(M, N)\) is an \(M\times N\) matrix with elements drawn from a normal distribution with a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 0.01.

3 Results and discussion

In this study, we employed a combination of publicly available libraries, namely Qiskit (Qiskit Nature 0.3.2, Qiskit Aer 0.12.0, and Qiskit Terra 0.24.0) [56] and PyTorch 1.11.0 [57] to implement the RO-VQE algorithm. To optimize the orbital rotation matrix \(\widehat{V}\) while keeping the variational parameters \(\theta\) fixed, we applied the projection method with alternating Barzilai–Borwein steps [58]. The implementation adapts the available codebase and leverages PyTorch’s tensor operations to improve computational efficiency. For the subproblem involving energy minimization with respect to θ, the algorithm utilizes the VQE implementation provided by Qiskit.

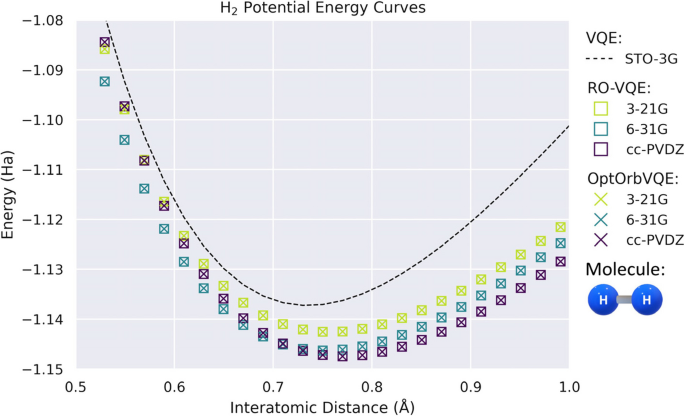

To assess the performance and adaptability of the RO-VQE and OptOrbVQE algorithms, we conducted simulations on H2, H4 in square geometry, and H4 in linear geometry, using various basis sets and qubit configurations. The results are presented and analyzed in terms of the resulting potential energy curves (PECs), as illustrated in Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6.

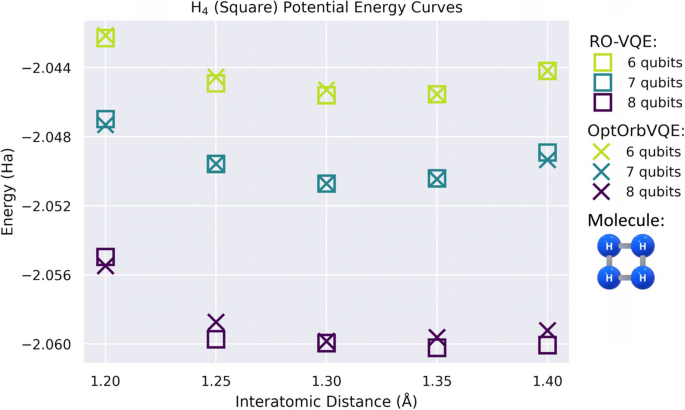

Potential energy curve of the H4 molecule in square geometry using the 6-31G basis set with varying qubit numbers (6, 7, and 8). RO-VQE (squares) and OptOrbVQE (crosses) yield lower energy as qubit count increases, with a slight difference seen at 8 qubits. This demonstrates that the effect of orbital selection is seen in larger qubit availability

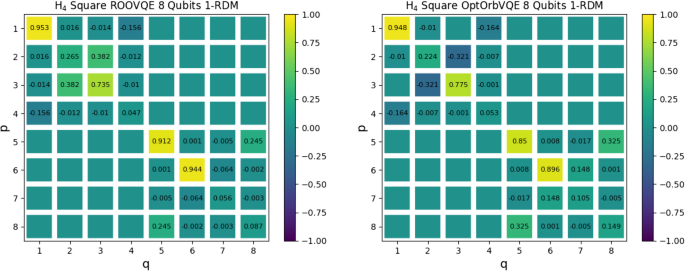

One-electron reduced density matrices (1-RDMs) of the H4 molecule in square geometry using RO-VQE (left) and OptOrbVQE (right) with 8 qubits. Diagonal elements represent orbital occupations, while off-diagonal elements indicate electronic coherences. RO-VQE exhibits a broader distribution of occupations and stronger off-diagonal terms, suggesting a more delocalized and correlated electron density compared to the more localized pattern in OptOrbVQE

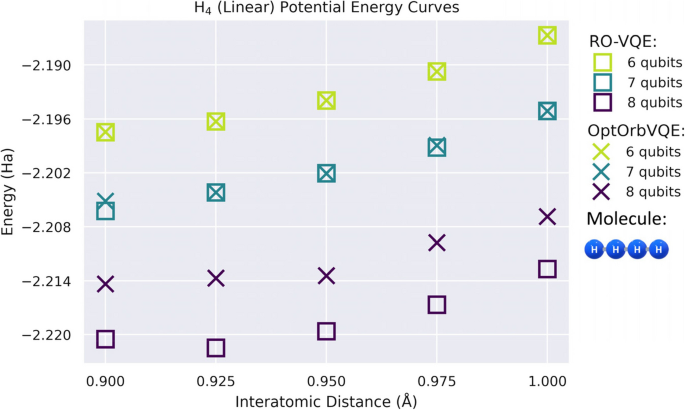

Potential energy curve of the H4 molecule in linear geometry using the 6-31G basis set and qubit counts of 6, 7, and 8. RO-VQE and OptOrbVQE produce closely aligned results, especially at 6 and 7 qubits. The linear system shows greater energy difference at 8 qubits, and the high consistency of RO-VQE across configurations highlights its robustness even under strong correlation

One-electron reduced density matrices (1-RDMs) of the H4 molecule in linear geometry using RO-VQE (left) and OptOrbVQE (right) with 8 qubits. Both methods yield nearly identical diagonal and off-diagonal structures, reflecting highly localized electron density and minimal orbital correlations. This similarity highlights the reduced impact of orbital selection strategies in simpler, symmetry-constrained systems like linear H4

Potential energy curve of the H2 molecule simulated using VQE with a fixed number of qubits (4) and varying basis sets (STO-3G, 3-21G, 6-31G, cc-pVDZ). Both RO-VQE (squares) and OptOrbVQE (crosses) show nearly identical energy profiles across all interatomic distances, indicating consistent performance across orbital selection strategies in a minimal qubit setting

3.1 Varying number of qubits

To investigate the impact of qubit count on the accuracy of VQE algorithms, we conducted simulations on the H4 molecule in both square and linear geometries using a fixed basis set (6-31G), while varying the number of qubits from 6 to 8. Both RO-VQE and OptOrbVQE algorithms were applied to assess the effectiveness of random versus energy-based orbital selection strategies as additional quantum resources become available.

As illustrated in Fig. 2, a clear and consistent trend is observed in the square geometry: increasing the number of qubits results in progressively lower total energy values, reflecting improved accuracy in approximating the ground-state wavefunction. With only 6 qubits, the active space is restricted, yielding the highest (and thus least accurate) energy estimates. The 7-qubit results show moderate improvement, while the 8-qubit configuration achieves the lowest energies, indicating the most accurate approximation. This outcome aligns with the principles of quantum simulation, where a larger number of qubits allow for the inclusion of more spin orbitals, thereby enhancing representational capacity and energy precision.

When comparing RO-VQE and OptOrbVQE, the performance gap is relatively small, particularly at 6 and 7 qubits. In some regions, such as around 1.25 ˚AÅ, 1.30 ˚AÅ, and 1.40 ˚AÅ for the 6-qubit case, RO-VQE slightly outperforms OptOrbVQE, likely due to favorable random orbital selections. As the qubit count increases to 8, the PECs from both methods become distinguishable, suggesting that RO-VQE’s randomly selected orbital subsets can surpass OptOrbVQE when the active space is sufficiently large. This convergence illustrates the diminishing influence of orbital selection strategy in higher-qubit scenarios.

Another key observation from RO-VQE in 8 qubits is the smooth energy curve as a function of bond length. Notably, RO-VQE exhibits no erratic fluctuations despite its stochastic nature, highlighting its robustness in symmetric systems such as square H4, where multiple orbital subsets may provide equally accurate representations.

To further support these energy trends, we analyzed the 1-RDMs for both RO-VQE and OptOrbVQE at the 8-qubit level (see Fig. 3). These matrices provide insight into how orbital occupations and electron correlations are distributed in each ansatz.

From the diagonal elements, we observe that both methods yield strongly occupied orbitals, particularly orbitals 1, 3, 5, and 6, but with distinct distribution patterns. RO-VQE shows higher occupation on orbitals 1 (0.953), 3 (0.735), 5 (0.912), and 6 (0.944), but also non-negligible populations in orbitals 2 and 8, reflecting a broader utilization of the available orbital space. In contrast, OptOrbVQE concentrates occupation more narrowly in orbitals 1 (0.948), 3 (0.775), 5 (0.850), and 6 (0.896), with smaller contributions from the others. This indicates that RO-VQE tends to distribute electron density across a slightly wider subset of orbitals.

Off-diagonal elements, which indicate coherence or correlation between orbitals, further distinguish the two methods. RO-VQE displays modest but notable off-diagonal values (e.g., 0.382 between orbitals 2 and 3, 0.245 between 5 and 8), suggesting a more delocalized and correlated representation. Meanwhile, OptOrbVQE yields smaller and more localized off-diagonal values, indicating that its energy-optimized orbitals are more decoupled.

These observations suggest that RO-VQE’s stochastic selection leads to a richer entanglement structure and a smoother adaptation to bond length variations, which aligns with the previously observed robustness and smoothness of its potential energy curve. The broader occupation and coherence structure may enable RO-VQE to capture dynamic correlation effects more flexibly, particularly in symmetric systems like square H4, where many orbital configurations are nearly degenerate.

The overall energy trends observed in the linear geometry (Fig. 4) closely mirror those of the square configuration: increasing the number of qubits consistently results in lower total energy values across all bond lengths. With 6 qubits, both RO-VQE and OptOrbVQE yield the highest energies due to the restricted active space. Increasing the qubit count to 7 provides moderate improvements, while the 8-qubit configuration achieves the lowest energies, indicating that an expanded variational space significantly enhances the accuracy in approximating the ground-state wavefunction.

Using 6 qubits, RO-VQE and OptOrbVQE produce closely aligned energy estimates. Furthermore, for 7 qubits, RO-VQE occasionally yields slightly lower energies at certain bond lengths, such as at 0.900 ˚AÅ and 0.975 ˚AÅ. As the number of qubits increases to 8, the energy curves from both methods have significant difference, suggesting that randomly selected orbital subsets in RO-VQE may, by chance, capture critical correlation effects more effectively than MO-based selection. In other words, the distinction between random and MO-based orbital selection becomes visible at higher qubit capacities.

The absence of erratic behavior in RO-VQE, despite its stochastic nature, reflects the method’s robustness. In symmetric and strongly correlated systems such as linear H4, multiple orbital combinations can lead to similarly accurate approximations, reinforcing the reliability of RO-VQE under different orbital configurations.

To further understand the energy behavior in the linear configuration, we also examined the 1-RDMs obtained from RO-VQE and OptOrbVQE using 8 qubits (see Fig. 5).

In contrast to the square geometry, both methods yield very similar 1-RDM profiles for the linear configuration. The diagonal elements are nearly identical, with orbital occupations of ∼0.988 and ∼0.971 for orbitals 1, 2, 5, and 6, while the rest remain close to zero. This pattern indicates a highly localized electronic distribution, consistent with the less entangled and more symmetry-constrained nature of the linear H4 system.

The off-diagonal elements are also notably small (mostly within ± 0.03), and again largely match between RO-VQE and OptOrbVQE. This suggests that in the linear configuration, the correlation structure is relatively simple and does not require extensive coherence across orbitals. Thus, both random and energy-based orbital selection strategies lead to similar 1-RDM structures.

The agreement in 1-RDMs explains the closely aligned energy curves, particularly at 6 and 7 qubits, and also supports the observation that the linear geometry inherently limits the diversity of useful orbital subsets. Even when more qubits are available, the relatively simple correlation in linear H4 causes RO-VQE and OptOrbVQE to converge toward the same solution structure, highlighting the reduced sensitivity to orbital selection strategies in this case.

This further reinforces the robustness of RO-VQE: even in geometries where fewer correlated configurations are viable, RO-VQE is still able to select effective orbital subsets, producing results on par with more deterministic methods like OptOrbVQE.

In summary, these simulations highlight the critical role of qubit availability in improving the accuracy of VQE-based energy estimations for linear H4. While OptOrbVQE and RO-VQE show negligible differences at lower qubit counts, RO-VQE proves to be highly competitive, achieving near-identical performance at 8 qubits. These results indicate that RO-VQE is a viable and efficient alternative for modeling strongly correlated systems, particularly when sufficient qubit resources allow for the inclusion of larger orbital subspaces.

3.2 Leveraging bigger basis sets

Afterwards, we discuss the H2 molecule simulation. The PEC of the H2 molecule was calculated using a fixed number of qubits (4 qubits) while varying the basis sets to evaluate the performance of RO-VQE and OptOrbVQE in different orbital spaces. The basis sets used include 3-21G, 6-31G, and cc-pVDZ, which represent progressively larger and more flexible descriptions of the electronic structure. For reference, the conventional VQE result using the STO-3G basis set was also included.

As illustrated in Fig. 6, the STO-3G VQE curve serves as a baseline, producing a relatively shallow PEC due to the limited flexibility of the minimal basis. In contrast, both RO-VQE and OptOrbVQE outperform this reference across all interatomic distances, with the most significant improvements observed near the equilibrium bond length. These gains can be attributed to the increased representational power of the larger basis sets, which allow for more accurate modeling of the electronic wavefunction despite the fixed qubit budget.

A clear trend emerges: for both RO-VQE and OptOrbVQE, energy values decrease systematically as the basis set size increases. The 3-21G basis yields higher energies compared to 6-31G, while cc-pVDZ produces the lowest energy estimates across the entire PEC. This consistent behavior highlights the critical role of basis set quality in enhancing accuracy under qubit-limited conditions.

Notably, RO-VQE and OptOrbVQE deliver nearly identical performance for each basis set, with their energy profiles closely overlapping throughout the full range of bond distances. This observation suggests that the randomly selected orbital subsets in RO-VQE are often sufficient to capture the essential low-energy states, rivaling the performance of MO-based selections in OptOrbVQE. As such, RO-VQE presents a viable and potentially more scalable alternative, particularly in scenarios that require rapid exploration of multiple orbital configurations.

4 Conclusions

This study compared OptOrbVQE and RO-VQE in simulating the ground-state energies of H2 and H4 molecules using VQE under two scenarios: varying basis sets with a fixed number of qubits (H2) and varying qubit counts with a fixed basis set (H4). The results show that RO-VQE performs comparably to OptOrbVQE across all cases, even occasionally yielding slightly lower energies at certain geometries.

For H2, both methods produced nearly identical results across different basis sets when using four qubits. For H4 (square and linear), increasing the number of qubits consistently improved energy accuracy, and the difference between RO-VQE and OptOrbVQE is seen significantly at higher qubit counts. This indicates that the impact of orbital selection strengthens as more qubits (and thus orbitals) are included.

Overall, RO-VQE demonstrates reliable and stable performance despite its random orbital selection, making it a practical and computationally inexpensive alternative, especially in systems where enough qubits are available to capture essential correlation effects.