1 Introduction

The first document on the energy source of the stars and sun [1] opened a century-long dream of fusion energy. The theory of quantum tunneling to overcome the Coulomb barrier was critical for the possibility of laboratory fusion energy development. Through long research on developing fusion plasmas, an apex of fusion plasma research was reached with three large tokamak eras (TFTR, JET, and JT-60U). The discovery of improved confinement regimes and relevant scaling laws supported by confinement physics models were the basis of the current ITER project and other DEMO programs throughout the world.

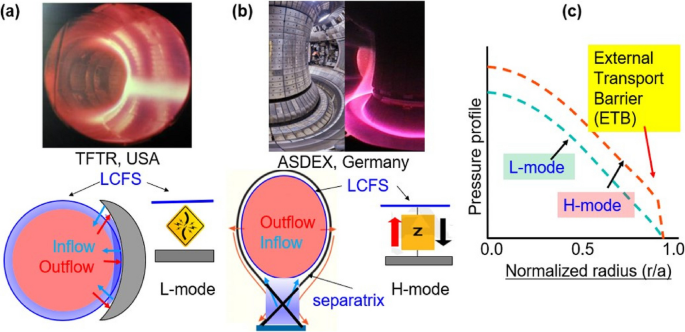

This paper critically reviews the causality of improved energy confinement regimes in toroidal magnetic devices, energy confinement scaling laws, and performance data. Following the discovery of high confinement mode (H-mode) in tokamak plasmas, when a diverted magnetic configuration with an x-point between the last closed flux surface (LCFS) and divertor plate surface was introduced in ASDEX, Germany [2], shaped plasma with divertor configurations has dominated over circular plasmas with limiters. In H-mode plasmas, the improved confinement region has been dominantly at the edge region compared to that of the L-mode plasmas, and it has been labeled as an edge transport barrier (ETB). Initially, H-mode pedestal pressure was pronounced by edge Te and slowly evolved to ne dominant pedestal. There are reports on improved confinement between L-mode and H-mode such as QH-mode and I-mode and edge pedestal of divertor system at lower field side (negative triangularity). The research effort on formation of ETB has been mostly focused on suppression mechanisms of the various gradient driven turbulences through ErxB effect.

A new model for edge confinement based on the interplay between inflow and outflow plasmas across the LCFS is suggested in this paper. Here, the “inflow plasmas” are defined as the plasmas transported across the LCFS originating from divertor surfaces (i.e., high recycling rate), and “outflow plasmas” are the plasmas transported across LCFS to the surfaces of divertor. A new potential source of Er inside the LCFS is suggested, possibly due to ∇B drift in the vicinity of the x-point, and this is compared with conventional turbulence suppression mechanisms via ErxB effects through measured edge turbulences. The source of high turbulence observed at the edge of the L-mode plasmas in both limiter and diverted plasmas can be from the inflow plasmas, and the turbulence part can induce enhanced particle transport which enhances the outflow plasma which can provoke more inflow plasmas until the surface of limiter and divertor is well conditioned.

In this new model, another quantity useful for edge confinement of the closed magnetic confinement system is the “flow impedance” which represents impedance of the plasma flow between LCFS and the surfaces of divertor plates. This concept is employed to explain the variation of edge confinement of toroidal devices and can be applied in the design of a divertor system for an optimum flow impedance that can effectively control the inflow plasmas and the required heat dissipation. Examples are “super-x” and “snowflake” that have a long leg of x-point between LCFS and divertor plates; however, smarter design may be needed for compact device. As the heating power level increased, improved confinement was observed in the core region, and this regime was labeled as an internal transport barrier (ITB). The ITB is based on a steep pressure gradient formed near the core region of the plasma, and formation of ITB in the core has been observed in both edge magnetic configurations with limiter and divertor. The improved confinement inside the ITB has been attributed to the turbulence suppression mechanisms like hi marginality and the breaking of streamers via ErxB effect or q-profile shear [3]. But there is no coherent model that supports ITB formation other than that ITB formation cannot be obtained without effective core heating.

An auxiliary heating system is essential to achieve high ion temperature (Ti > 10 keV) essential for ignition regime where sufficient α-particle power can sustain ignition state in fusion devices. The heating method is divided into two categories: electron heating and ion heating. Direct ion heating by positive neutral beam (PNB) has been effective, but application to a large device and/or high-density plasmas is challenging. On the other hand, application of electron heating in high density and/or large devices can be effective, but there are unresolved issues such as central density pump-out, early saturation of ion temperature, and no high-power experimental data (> 10 MW). Notably, ITER plans to include ~80 MW of electron cyclotron resonance heating (ECRH) system.

The confinement time scaling and performance data accumulated for half a century are examined to project a logical path for the most probable compact ignition test device in magnetic fusion. For practical fusion energy production, it is imperative to build experience with an ignition test device that can produce sufficient fusion power prior to electricity generation. These experiences include comprehensive actuators for control of performance and stability, fusion material test, and power conversion system. A tokamak device with plasma volume of ~240 m3 with PNB power < 40 MW is a probable candidate. The goal of this test device is fusion power output of ~220 MW at a moderately high density. With this level of fusion power, α-particle power up to ~60 MW may be sufficient to test the ignition state as well as transition physics from external (PNB) to internal α-heating.

2 History of fusion research and magnetic fusion

The first document on fusion possibility was published in 1929 by Atkins and Houterman [1], suggesting that the energy source of stars might be from fusion reactions. Eventually, the fusion reaction was demonstrated by Oliphant, and Sir Rutherford proposed the “Moonshine” project for fusion energy development based on beam-target experiment [4]. A theoretical breakthrough came from G. Gamow who suggested a feasibility of practical fusion reaction at ~10-keV ion temperature through quantum tunneling to overcome the Coulomb barrier in 1935. H. Bethe established the fusion energy cycle of the sun, which explains the ~5 billion years lifetime of the sun in 1939, and he received the Nobel Prize in 1967. Among various fusion reactions, the most practical fusion reaction in the laboratory is deuterium-tritium (DT) reaction which has sufficient cross section at ~10–20-keV ion temperature, while the next approachable reaction of deuterium-He3 reaction requires ~100 keV. A self-sustainable fuel for DT reaction is feasible through lithium which can produce tritium with abundant deuterium from ocean water. However, self-sustained tritium production has yet to be demonstrated due to lack of adequate neutron source.

Many laboratory experiments have been conducted using various magnetic confinement concepts, and they are divided into two categories: open and closed magnetic configurations. Examples of open systems include pinch devices and magnetic mirrors; closed systems include spheromak, field-reversed configuration (FRC), stellarator, and tokamak. In general, the closed system performed better than the open system which has intrinsic loss mechanisms. The early experiments of closed system were hampered by numerous instabilities, and the first promising confined plasma was demonstrated in T3 tokamak, the former Soviet Union. Here, the electron temperature was measured to be ~1 keV by British scientists in 1958. Since then, many stellarators and tokamaks have been challenged by Japan, Europe, Russia, and the USA. Early research devices were based on water-cooled Cu magnet, and the discharge was based on a short pulse due to limitation of cooling. The representative experimental devices were TFTR, USA; JT-60U, Japan; and JET, EU. TFTR and JET are only fusion devices which performed DT experiment, and JT-60U projected fusion power based on DD experiment. These three devices achieved roughly Q~1 (scientific breakeven) at ~40-MW heating power. However, the ignition state of magnetic fusion has never been demonstrated.

After successful demonstration of near “scientific breakeven” condition, steady-state capable devices with superconducting magnets have been developed to support steady-state plasmas (ignited plasma operation) for the future. Examples are LHD, Japan, and W7-X, Germany, for stellarator concept, and KSTAR, Korea, EAST, China, and SST, India, are for tokamak concept. The first international effort to achieve the goal of fusion energy development was briefly initiated in 1978 under the name of “INTOR,” and then it took a long time to be transformed into the ITER program in 1987. The proposed original ITER program was incredibly large device (i.e., VP > 2000 m3) based on L-mode confinement scaling law. Discovery of high confinement mode (H-mode) in a diverted plasma in ASDEX, Germany, opened a possibility of a smaller size ITER (VP ~900 m3). It took more than ~20 years to materialize a practical international fusion program, and construction of ITER is in progress at Saint Paul-les-Durance, France. The primary goal of ITER was to demonstrate ignition state through the DT experiment, and the planned first plasma in 2021 is delayed due to administrative and engineering issues. The new timeline for the first plasma will be ~2035 if ITER ever finishes construction in time. In recent years, there have been new private-public efforts to accelerate realization of fusion energy development in a much smaller device. They are STEP (https://step.ukaea.uk/) program in the UK and ARC of CFS (https://cfs.energy/), USA, while conventional approach with a large tokamak is still in progress such as CFETR [5], EU-DEMO [6], and K-DEMO [7].

3 Confinement physics of the plasma, heating system, and turbulence-based transport models

3.1 Edge confinement improvement (ETB) and magnetic configuration

Early toroidal devices (i.e., mainly stellarator and tokamak) were based on circular magnetic flux surface with a limiter configuration. As an example, a photo of poloidal cross section of a discharge in TFTR is shown in Fig. 1a. Here, a bright yellow glow is due to “ionization,” and this region is a potential source of plasmas from limiter surface. As shown in the schematic, the last closed-flux surface (LCFS) (i.e., boundary of the plasma) is in direct contact with the limiter surface. The outflow plasmas (red arrows) impinging on the limiter surface interact with limiter material and neutral gas inside the material of the limiter. The plasmas from ionization on the limiter surface must flow back to the LCFS, and the edge region (0.8 < r/a < 1.0) is a mixture of inflow and outflow plasmas as shown in this schematic (bluish color). The connection between LCFS and limiter surface is like an electric “short circuit.” The confinement mode in limiter configuration is characterized as an L-mode (i.e., discharges with low confinement). In early 1980 s, a noncircular magnetic configuration with divertor system was introduced in ASDEX device, Germany [2], together as shown in a photo in Fig. 1b. Here, glows (ionization) toward the divertor surfaces are shown in this photo. In the schematic of diverted plasma, the LCFS is indirectly in contact with the divertor plate through x-point as shown in this figure.

Photos and corresponding schematics of tokamak plasmas with limiter and diverter system. The glows in photos represent Hα light from ionization of neutrals and surface materials. Bluish color and blue arrows indicate inflow plasmas, and red arrows represent outflow plasmas. The gray color represents limiter or divertor materials. a A circular plasma of TFTR where the LCFS is directly in contact with the limiter surface, and the edge plasma is a mixture of inflow and outflow plasmas. Electrically, it is like a “short circuit.” b A single null plasma with divertor on ASDEX. The x-point is between the LCFS and divertor surface. The inflow and outflow plasmas experience a finite flow impedance. Electrically, it is like a finite impedance for the plasma flow between LCFS and divertor surface in the H-mode phase where inflow plasmas are limited below the LCFS. c Pressure profiles are schematically shown for the L-mode and H-mode with external transport barrier (ETB)

Therefore, inflow and outflow plasmas between LCFS and divert or surface have a finite Z-value instead of Z = 0 (“short circuit”) for limiter case, where Z represents a flow impedance. In this magnetic configuration, a new high confinement mode (i.e., H-mode) through a sudden transition from the L-mode was discovered, and the confined plasma energy was twice as high compared to that of the L-mode on average [2]. Empirically, a distinctive characteristic of the H-mode discharge was a high edge pressure pedestal and leveled as edge transport barrier (ETB) compared to that of the L-mode discharge as shown schematically in Fig. 1c. Classification of the H-mode is based on higher edge pressure pedestal (ETB) accompanied by dithering spikes in Hα-light (e.g., edge localized mode (ELM) burst) in general.

As discussed in the previous section, the difference in energy confinement time between the L- and H-modes was a factor of 2 on average. It is possible that the formation of the H-mode may arise from a sudden transition from the L-mode phase, and, similarly, the H-mode phase may transition back to the L-mode phase. Whether the toroidal device relies on limiter or divertor, conditioning of the contact surfaces of the limiters or divertors is a routine process of plasma operation. Carbon-based materials have been commonly used for the limiter and divertor surfaces. The goal of conditioning the contact surfaces is the reduction of inflow plasmas including impurities. The process consists of discharge cleaning with RF or low-power discharge cleaning (bombarding plasmas on the surface) as well as surface coating with materials with atomic numbers less than carbon such as beryllium, boron, or lithium. As the detention of tritium in porous carbon-based materials becomes a regulatory problem in ITER, nonporous high Z materials such as tungsten were introduced to avoid the tritium detention problem. The collapse of discharges due to the accumulation of tungsten in the core of the plasma experienced on the Princeton Large Torus (PLT) [8] was revived. It seems inevitable that the introduction of argon or neon seeding (massive gas injection) would be necessary to cool down the outflow plasmas below ~30 eV in order to suppress the ionization of the tungsten. As a result of massive gas injection near the divertor surface, it is inevitable to avoid performance degradation due to the increasing inflow plasmas. This process of massive gas injections may become a bigger problem as the device size increases.

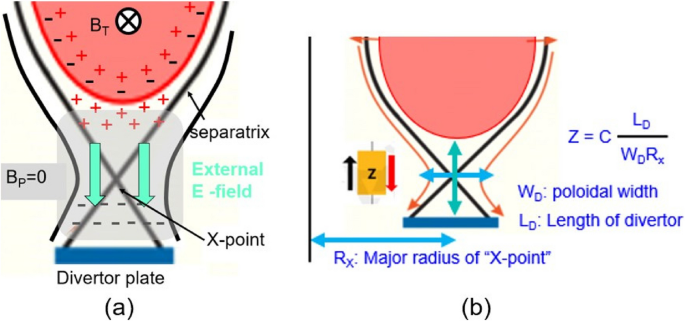

The formation of ETB has been attributed to turbulence suppression mechanisms via the ErxB effect in the pedestal region. The measurement of Er at the edge of the H-mode plasmas has been reported in many devices, but the source of the Er was attributed to the ion orbit loss in the vicinity of the x-point [9]. An alternative source of Er inside the LCFS can be a response to external E-fields from ∇B drift in the vicinity of the x-point where BP≅0 as shown in Fig. 2a. The induced Er inside the LCFS would then spread poloidally through rotational transform. Here, the “flow impedance” which is similar to electrical impedance than fluid impedance can be defined as follows:

where \({L}_{D}\) is the length from LCFS to divertor plate, \({W}_{D}\) is the poloidal width of divertor across the "x-point", \({R}_{x}\) is the major radius of “x-point,” and C is the proportional constant as shown in Fig.2b.

a A schematic of potential source of electric field (Er) inside the LCFS is shown as a response to the external E-field (blue arrows) arising from ∇B drift in the vicinity of x-point (BP ≅ 0). b The flow impedance is proportional to the distance between the LCFS and divertor plate and inversely proportional to the width and major radius of the x-point

The edge plasmas in the limiter configuration are a mixture of outflow and inflow plasmas as shown in Fig. 1a. If the inflow plasmas at the edge of the limiter plasma are indeed the primary obstacle of preventing the H-mode pedestal formation in the limiter configuration, it is not surprising to find that there has been no systematic study of the H-mode in limiter plasmas, with the exception of a few papers based on observation of a transient edge density swell (pedestal like) with dithering spikes (ELM like) in Hα light [10]. The inflow plasma is divided into two parts (density and turbulence), in order to understand whether one subcomponent is dominantly responsible for preventing H-mode edge formation in limiter plasmas. The turbulence part of the inflow plasma is likely responsible for enhanced cross-field particle transport of outflow plasmas (i.e., anomalous transport), while inflow plasma density likely contributes to the main plasma density which comes from main fueling.

On the other hand, in edge plasmas of divertor configuration, outflow and inflow plasmas between divertor plates and LCFS have a finite flow impedance as shown in Fig. 1b. It has been universally observed that the edge plasma fluctuates highly in the L-phase and is quiescent in the H-mode [11]. A turbulence-assisted enhanced cross-field transport of the outflow plasmas can thus manifest the L-mode edge. When inflow turbulence level at the edge pedestal is receded, a base transport mechanism (i.e., neoclassical transport) is recovered and could form the H-mode edge pedestal. Therefore, the fast interplay between inflow and outflow plasmas may explain the transition physics of L to H and H to L transition in diverted plasmas.

The new transport model based on inflow plasmas can be applied to many improved modes that resemble the H-mode pedestal (i.e., higher edge pressure pedestal formation). The ratio between turbulence and density in inflow plasmas can control the density and temperature of the pedestal in the following way, since the turbulence part enhances edge outflow transport, while the density part provides additional edge fueling as the main plasma density is fueled by injected neutral gas. The edge of first H-mode discovered in 1980 s consisted of pronounced Te pedestal compared to the ne pedestal which is like the “QH-mode” [12] and “I-mode” [13]. When a flux surface with negative triangularity (NT) [14] was introduced to the divertor system at the low field side, a similar edge like “I-mode” was discovered. The NT configuration has improved core confinement and the temperature pedestal in the edge as the edge density is close to that of the L-mode. Note that flow impedance (Z) in NT system is low due to Rx dependence. In these regimes (i.e., QH, I, and NT edge), the edge pedestal pressure is between that of the L-mode and below the ballooning limit (i.e., no ELM instability) of the H-mode. Note that there is no absolute edge plasma pressure level for any of these modes including nominal H-mode. In these intermediate improved modes, it is common to find that the density pedestal is close to that of the L-mode and temperature pedestal is close to that of the H-mode. Note that the QH- and I-mode reported edge harmonic oscillation (EHO) and semi-coherent oscillations (Alfven mode), respectively. The low edge density may be due to this oscillation which can be the same role of the turbulence from the inflow plasma in the H-mode.

In daily operation of the plasmas in the control room, operation starts with the L-mode where high inflow plasmas from the unconditioned divertor intrude across the LCFS. Then, the outflow plasma energy enhanced by the turbulence-assisted particle transport conditions the divertor surfaces until the inflow plasmas are reduced. In order to increase the conditioning level to reduce the inflow plasmas further, the heating power can be increased, adding energy to the outflow plasmas. When the turbulence level from inflow plasmas is reduced in the edge region, an edge pedestal can form due to the recovery of a base cross-field transport (i.e., neoclassical transport). This can be a typical scenario of L to H transition, and the heating power level that reduces inflow plasmas can be treated as a threshold power for transition. In a back-transition scenario, the increased outflow plasma or sudden burst of MHDs, as bulk plasma energy builds up in H-mode phase, can provoke increased inflow plasmas above the threshold level across the LCFS. A sudden intrusion of turbulence from this increase can in turn trigger enhanced cross-field particle transport of outflow plasmas. Since ETB formation is a unique characteristic of diverted plasmas, it is important to examine the role of the edge magnetic configuration of the diverted plasmas and establish a path to improve the divertor system as actuator for ETB. Analogies can be found in the design of “super-x” [15] and “snowflake” [16] divertor systems where the plasmas flow impedance between the LCFS and divertor plate is increased. This new edge plasma transport model can be used to design a smart diverter system that can control the inflow plasmas as well as an effective heat dissipation of the outflow plasmas.

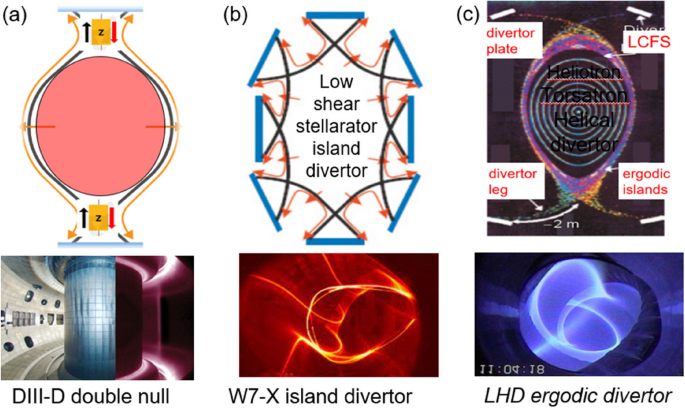

In addition to a single x-point magnetic configuration, a double null (two x-points) configuration was used in tokamak plasmas and the frequency of observing H-mode discharge was decreased on average. Consequently, the conditioning effort had to be increased compared to that of the single null operation as shown in Fig. 3a. This implies that the outflow and inflow plasmas are increased in double x-point configuration compared to those of the single x-point due to reduced flow impedance. As more x-points are introduced at the edge, the flow impedance is reduced further, and intense conditioning of the divertor plates is required to obtain any improved confinement at the edge. This model can be extended to the stellarators where edge islands form multiple x-points at the edge of advanced stellarator such as W-AS and W-7X [17]. However, the improvement factor has been less than that of tokamak plasmas on average. For example, a low shear island divertor can have several x-points, and a photo of W-7X divertor with glows at each x-points is shown together as shown in Fig. 3b. The LCFS of the heliotron/torsatron helical divertor is surrounded by ergodic islands as shown in the photo of LHD edge [18] in Fig. 3c. The ergodic divertor system is essentially equivalent to the limiter case where getting the H-mode edge is not feasible. This could explain the difficulty (or perhaps even the impossibility) of improving the edge confinement in stellarator. In summary, the total edge plasma flow impedance (Z) between LCFS and divertor plates can be represented as a parallel connection of flow impedance at each x-point:

where Zn is a flow impedance of each x-point. Note that the absolute flow impedance level for each device varies by the interplay between the inflow and outflow plasmas which is specific for each device and operation scheme. Therefore, it is difficult to quantify an absolute flow impedance level for the H-mode confinement that can be applied to the transport model. Nonetheless, this remains a useful physical concept that could potentially explain the edge confinement of the closed magnetic configuration with divertor or limiter.

Schematics and photos of edge magnetic configuration with multiple x-points are illustrated. In photos, glows near x-points are clearly illustrated. a Double null configuration of the DIII-D discharge. b Multi-island divertor systems employed in the low shear stellarator and a photo of the W7-X edge plasma. c Ergodic island divertor used in heliotron/torsatron devices and photo of LHD discharge with ergodic divertor. Figures are from ref. [18]

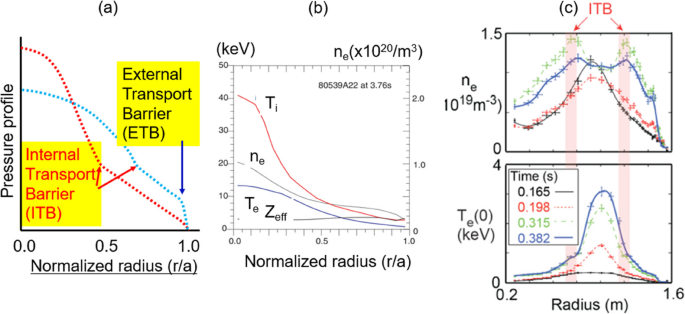

4 Core confinement improvement with ITB

Improved confinement in the core is characterized as a peaked pressure profile for ions and electrons with a steep pressure gradient labeled as an internal transport barrier (ITB) as shown schematically in Fig. 4a. In this figure, pressure profiles of one with narrow ITB and another profile with broadened ITB and ETB are illustrated. Note that the core beam fueling and/or core heating has been universal in core confinement improvement for toroidal devices regardless of the edge magnetic configuration (i.e., divertor and limiter). The edge condition that can influence effectiveness of the core heating is an optimum edge density for wave coupling requirements of RF heating and a lower edge density (i.e., control of inflow plasmas) for core heating beam penetration. Representative examples include a peaked ion pressure (Ti>Te) of the “supershot” in TFTR [19] as shown in Fig. 4b [20] and the peaked electron pressure (Te>Ti) of the plasma heated by higher harmonic radio frequency (HHRF) on NSTX [21] as shown in Fig. 4c.

a Schematics of pressure profile of improved core confinement with ITB alone (red dots) and pressure profile with ITB and ETB (blue dots) together are illustrated. b Ti, ne, Te, and Zeff profiles of the TFTR “supershot” (Ti > Te) where ITB is near r/a ~ 0.3–0.4 are shown. Figures are from ref. [20]. c Time evolution of Te and ne profile of the HHRF-heated plasma (Te > Ti) with ITB in Te profile on NSTX. Here, the core density pump-out is clearly illustrated. This figure is from ref. [21]

Note that the confinement regime with ITB has been observed in plasmas regardless of the edge magnetic configuration (i.e., limiter or divertor). Examples of improved core confinement discharges with the PNB system include the “supershot” and enhanced reversed shear (ERS) discharges [22] in limiter plasmas on TFTR. In divertor plasmas, examples include ITB discharges [23] or the FIRE mode in KSTAR [24], the hot ion mode in DIII-D [25] and JET [26], and the high βP regime in JT-60U [27]. It is not surprising to find a similar peaked ion pressure profile in different devices, since the beam line arrangement in most devices has almost identical tangential beam lines (i.e., TFTR, DIII-D, and KSTAR) except JT-60U. Since the main power was injected by perpendicular beam lines on JT60-U, high-performance plasma was obtained when the plasma position and size were compromised to have an effective core heating with intense divertor conditioning [27, 28] as shown in Fig. 5a.

As the H-mode confinement regime casts hope for a smaller fusion device than the device based on L-mode discharges, the plasma regimes with both ITB and ETB are even more promising for ignited plasma in a smaller magnetic fusion device. In this regard, a shaped plasma with divertor configuration has advantages over the circular plasma with limiter. They are control of inflow plasmas and flexible geometric factors for access of heating beam such as elongation, triangularity, and reverse D-shape. An example of such confinement mode with both ITB and ETB is “super H-mode” observed in a PNB-heated plasma (DIII-D) and ICRF-heated plasma (C-MOD) [29] as shown in Fig. 5b and 5c, respectively.

Examples of best performance discharges. a The record performance discharge on JT-60U with broadened ITB position with on- and off-axis PNB heating with extreme conditioning of the divertor system. b A discharge with broadened ITB (Ti > Te) and ETB (“super H-mode”) achieved with PNB heating (on-axis and off-axis) on DIII-D. c A high-performance discharge with ICRH-heated discharge (Te > Ti) on C-mod. A hint of density pump-out is shown in the core density. (A discharge with broadened ITB (Ti > Te) and ETB (“super H-mode”) achieved with PNB heating (on-axis and off-axis) on DIII-D). a is from ref. [28], and b and c are from ref. [29]

Since the ITB formation is common for plasmas in both divertor and limiter setups, it is reasonable to understand that the ITB formation may not be directly associated with the edge magnetic configuration, and it is likely associated with actuators such as an effective localization of the core heating source. It is imperative to establish practical actuators for ETB and ITB through comprehensive understanding so that global energy confinement can be further optimized and controlled in a given geometry.

4.1 C. Auxiliary heating systems in toroidal devices

Toroidal fusion devices need auxiliary heating to increase the core ion temperature well above ~10 keV for optimum fusion reaction condition of DT plasmas. Ultimately, core heating with α-power will be the only heating source in ignited plasmas, and there are two heating systems to generate sufficient α-power; they are ion or electron heating systems. In principle, the heated plasma species (ions or electrons) will exchange energy with each other, and the temperature is expected to be equalized in an equipartition time scale (Teq~Te3/2/ne). The condition for equalized temperature in ignited plasmas could be ne >> ~2 × 1020 m−3 as illustrated in Fig. 5c. Then, there is no distinction between heating system except engineering issues and required power levels. In this figure, pressure profiles of “super H-mode” plasmas heated with PNB (Fig. 5b) and ICRF (Fig. 5c) are illustrated. In the plasmas heated by PNB and ICRF, the ratio of Te/Ti~0.5 at ne~0.8 × 1020 m−3 and Ti/Te~0.85 at ne~2.0 × 1020 m−3, respectively. The gap between ion and electron temperature can be reduced by increasing the operating plasma density. Note that the operating density can be increased using high plasma current and/or magnetic field but decreases as the size is increased. It is important to review experimental results for the optimum choice of heating path to ensure sufficient α-power generation.

The ion heating system has two branches. The first involves direct ion heating through charge exchange with a low-energy positive neutral beam (PNB). The second involves heating a high-energy tail via negative neutral beam (NNB) with beam energy above ~250 keV and ion cyclotron resonance heating (ICRH) via resonance or direct damping of the wave energy. Among ion heating systems, NNB and ICRF are efficient in increasing the electron temperature even though they primarily heat ions, since the fast ions at the high beam energy (> 250 keV) lose energy primarily to electrons as demonstrated in LHD plasmas. Only the PNB system increases bulk ion temperature effectively, and practically speaking, the highest beam energy can be ~120 keV. There is ample experimental data with the direct ion heating system, and the highest α-power generated by the ion heating system was close to ~5 MW. Correlation between the core PNB heating and/or fueling and improved core confinement was extensively studied in TFTR plasmas [30, 31]. Here, a designed scaling study of the global confinement time of the plasmas heated by PNB with beam energy of ~100 keV including “supershot” regime showed that τE is linearly proportional to the peakedness of beam fueling profile [30]. The peakedness of the beam fueling profile is defined as a ratio of core beam fueling and volume averaged beam fueling. Data from high-βP regime in JT-60U [27] was well aligned with the “supershot” data from TFTR [32]. The core confinement was further improved by radially expanding the ITB position up to r/a~0.6. The Ti profile with the highest performance discharge in JT-60U [33] is shown in Fig. 5a. Here, the position and size of the plasma were compromised so that one of the perpendicular beam lines was aimed at the center while the other one was aimed at r/a~0.25 [28], while an extremely low edge density was sustained as shown in Fig. 5a. Another example is the “super H-mode” [29] on DIII-D, which was obtained with a combination of tangential beam lines and an off-axis PNB system as shown in Fig. 5b. It was shown that direct ion heating is extremely effective in increasing ion temperature above ~10 keV, but electron temperature is saturated in all discharges with high ion temperature as shown in the “supershot” (Fig. 4b) and super H-mode (Fig. 5b).

If the choice of heating is PNB system which has demonstrated achieving high ion temperature, the initial plasma with Ti/Te > 1 at moderately high density can switch to ignited plasmas with higher density through DT fueling so that electron heating by α-particles can thermalize fast to sustain Ti~15 keV. At the same time, a gate valve with sufficient neutron shielding can block the access of PNB beam lines.

It is critical to understand the electron heating process to reach the ion temperature optimum for ignition state (Ti > 10 keV), since α-particle power at 3.5 MeV is the only heating source once the ignited plasma state is established by the external heating. In electron heating experiments, similarly peaked Te profiles were observed in numerous heating experiments by ECRH [34]. Examples of radiofrequency (RF) heating are HHRF [21] heated plasmas in NSTX (Fig. 4c) and ICRF-heated plasma in C-MOD as shown in Fig. 5c. In both figures, it is evident that there is a signature of core density pump-out during the RF heating period. The electron heating system is based on the dissipation of wave energy through resonance like low-hybrid heating (LH) and ECRH [35]. Empirically, in plasmas with electron heating systems (LH and ECRH), the electron temperature is increased, while the ion temperature is clamped at the lower temperature compared to that of the electron (Ti<<Te) [36]. The observed density pump-out and clamping of Ti problem in electron heating system are serious issues.

If there is any experimental experience at higher electron heating power > 10 MW or a plasma with Ti > 10 keV, it would be easier to estimate the power level to reach the ignition state. Any device based on an electron heating system may have to prepare up to ~50 MW, since the power level used in PNB was ~40 MW and ~50 MW α-power would be sufficient to test the ignition state. Thus, it is also important to consider how to deliver such high power to the plasma.

4.2 D. Transport models for ITB and ETB and experimental data

Among numerous transport models for ITB, a few popular models will be examined, with attention paid to consistencies and inconsistencies in the experimental results. Following discovery of the “supershot” in TFTR [20], similar improved discharges with similar and different ITB positions and pressure profile shapes have been reported with various names, as if it is unique for each device. Considering each device has different beam line arrangements, beam energy, plasma shape, and density profile, it is not surprising that the ITB position ranges from r/a = 0.3 to 0.6. Note that the improved core confinement with high ion (or electron) temperature can be achieved as long as the heating power is deposited in the vicinity of the core region of the discharges in both L-mode and H-mode edges as discussed in the previous section. ITBs in ICRF and ECRH heated discharges are within r/a~0.2 except a broad ITB and ETB in C-MOD as shown in Fig. 5c.

Interpretation of the improved confinement with edge pedestal formation (ETB) and steep pressure gradient near the core (ITB) is mostly based on turbulence suppression mechanisms due to the pressure gradient condition, velocity shearing rate, and core region q-profile shape deviating from monotonic profile. (1) The first example could be the ηi(=Lne/LTi) marginality condition in ITG mode suppression [37] where Lne is the density and LTi is the ion temperature scaling length, respectively. The condition of the ITG mode suppression for the “supershot” was ηi~3–5, and this value was more or less the same for the measured profiles of the “supershot” case. As experimental data was accumulated, a wide range of measured values for ηi was observed. For example, even it can be infinite for the broadened ITB in “super H-mode” case where the density profile is flat as shown in Fig. 5b. (2) The second example comes from various core magnetic shear from weak shear to reverse shear. There are many reports on the improved core confinement (peaked ion pressure profile) based on the shear of the q-profile, and q-minimum position coincides with the position of ITB [3, 38]. Note that the q-profile shape in the core can easily be modified via a driven heating beam current. Isolation of the ITB position from modified q-minimum position due to heating beam current [39] should be clarified, in order to validate the causality. (3) The most popular example is turbulence suppression due to poloidal rotation profile shear of the plasma arising from ErxB effect. An example of ITB formation due to this mechanism in the core [22] and edge region for ETB formation [40] shares the same basic idea. The improved confinement is through the breaking of semi-coherent turbulence structures such as streamers and ITG mode which are thought to be responsible for a rapid loss of plasma energy as demonstrated through simulation [41]. Note that measurements of poloidal shear, Er and identification of turbulence in the core (Fig. 6) are non-trivial, and reliable data are limited. Er well inside the LCFS of the H-mode has been confirmed by numerous measured Er at the edge of the plasmas [45, 47]. Theoretical prediction of Er well was given based on ion orbit loss near x-point using gyrokinetic simulation [42], and the prediction was consistent with the measurement in most of the H-mode edge experiments. In a comparative experimental study of positive triangularity (PT) and negative triangularity (NT), edge confinement of the H-mode edge in PT was higher than that of the NT on AUG [14] as shown in (Fig. 8) of this reference. The core confinement of NT on TCV [14] was higher than that of PT when PNB was used, and this difference may be due to effective core heating in NT. The recent comparative gyrokinetic simulation of ion orbit loss in the geometry of NT and PT reported that the Er well in NT is higher than that of PT [9]. Therefore, improved edge confinement is expected in NT configuration rather than PT configuration.

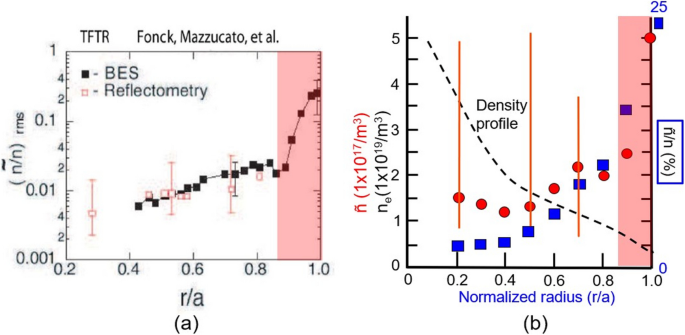

a The full profile of normalized turbulence (ñ/n) of the “supershot” discharge on TFTR. Variation of ñ(r)/n(r) is entirely due to typical density gradient of “supershot” except at the very edge. Considering a peaked density profile, (ñ(r)) level is almost constant up to r/a ~ 0.9, and the value is extremely low (1–2 × 1017/m3). Note that recycling coefficient is R ~ 0 for the edge of the “supershot.” High turbulence for r/a > 0.9 may be characteristic of the edge of the highly conditioned limiter plasma. Figure 6a is from reverence 46

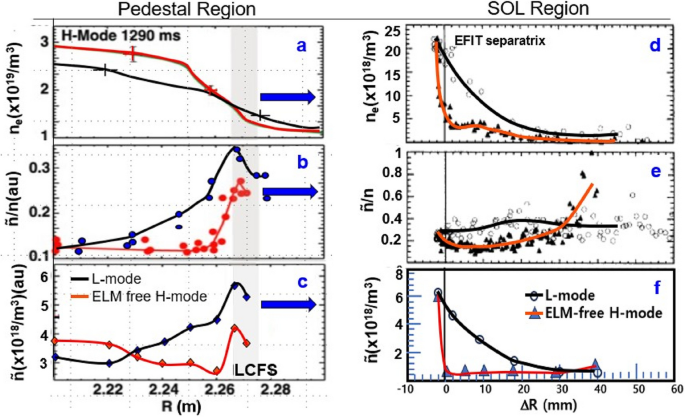

This is the best example of turbulence suppression model via the ErxB effect responsible for edge confinement improvement. Density profile and normalized (ñ/n) and absolute (ñ) turbulence levels of the L- and H-mode phases are shown for pedestal region (a, b, c) and SOL region (d, e, f). Figures are from refs. [47] and [48]. In the H-mode phase, outflow plasmas are reduced in the pedestal and inflow density, and turbulence are reduced in the SOL region. In the L-mode phase, inflow plasmas (density and turbulence) are increased in the SOL region, and outflow plasmas are increased due to the turbulence enhanced outflow transport. Note that (ñ) is constant in the H-mode phase and higher (ñ) in the L-mode phase at the LCFS decreases and merges to that of the H-mode

The ITER 98 τE scaling law and a target confinement time (~ 2.4 s) for the most probable compact ignition (green box) are shown in this figure. The scaling law is dominated by plasma volume as demonstrated in Table 2. The corresponding τE ~ 1.6 s (black cross) assuming H-factor of ~1.5 and projection of ITER τE are indicated

A potential alternative source of Er inside the LCFS in H-mode can be due to the external E-field induced by ∇B drift of the plasmas in the vicinity of the x-point where the poloidal field (BP) is close to zero as shown in Fig. 2. This is similar to the classical ExB effect on the equilibrium of the toroidal plasma without poloidal field. Inside the LCFS region close to the E-field, electrons accumulated in response to the positive charges outside the LCFS resulting in a negative Er. The induced Er will spread to the same flux zone through helicity, while the external E-field will be confined in the vicinity of the x-point. This ExB drift of the plasmas between LCFS and divertor may be responsible for the observed high density and high turbulence level in the outer-leg of the divertor region [45]. In visible images of the divertor system, it is common that the intensity of the outer leg is brighter than that of the inner leg.

There is an excellent review of many experimental measurements of turbulence and Er at the pedestal as well as the scrape-off layer (SOL) in the edge plasmas [46]. In general, the frequency spectra have bandwidth < ~1 MHz, and dominant low frequency is universal as long as Doppler shift due to plasma rotation is corrected and long wavelengths are dominant. Both frequency and wavelength spectra are more or less the same for all measurements in toroidal devices.

A full profile of turbulence measured by BES and reflectometry in a “supershot” discharge which has ITB in the core density and Ti profiles and edge of extremely well-conditioned limiter plasmas in TFTR is illustrated in Fig. 6a [46]. A high-level turbulence (ñ(r)/n(r)~20%–30%) at LCFS rapidly drops to ~2~3% level at about r/a = 0.9. Then, a rapid decrease of (ñ(r)/n(r)) from ~2~3% to ~0.4% near the core is illustrated in Fig. 6b, and this is largely due to peaked density profile in “supershot” discharge as shown in Fig. 6b. The unnormalized ñ(r) profile is almost flat for the region of r/a < ~0.8, and the absolute value of ñ(r) is ~1–2 × 1017/m3 with a large uncertainty. The ñ(r) increases rapidly considering the mild density gradient in the edge as shown in Fig. 6b. The excess part of density turbulence (ñ(r)) can be attributed to inflow turbulence from the limiter. Note that the beam fueling rate is ~1017/m3 s in the core region, and one neutral beam ion carries one cold electron.

There are many papers on the measurement of edge turbulence and different suppression mechanisms for improved confinement at the edge region [45]. However, there is no local measurement of relevant plasma parameters in the vicinity of the x-point, and measurements are near the midplane. Therefore, quantities like inflow/outflow plasma density and turbulence can be highly asymmetric. An excellent example of turbulence suppression due to the ErxB effect with full set of profiles in a diverted plasma (DIII-D) will be examined. A comparative study is given with the measured profiles of density, turbulence, Er, and velocity shear at the edge (r/a = 0.85–1.0) [47] and SOL region (r/a > 1.0) [48] of the L-mode and ELM-free H-mode phase in quiescent Ohmic plasmas. As shown in the reduced set of data in Fig. 7, the correlation between the normalized turbulence level (ñ(r)/n(r)) and density profile at the edge of the L- and H-mode phase represents a clear suppression of turbulence due to VErxB in H-mode phase. In the L-mode phase, the level of the ñ(r)/n(r) is ~20–30% higher than that of the H-mode phase at the LCFS region and gradually merges to the H-mode level at r/a = 0.85 as shown in Fig. 7b. This result can be paired with the measurements in SOL region as shown in Fig. 7e. In the L-mode phase, ñ(r)/n(r) is 20~30% at the LCFS and is almost constant across the SOL. In the H-mode phase, ñ(r)/n(r) starts with the same magnitude as the L-mode before briefly dropping by a of factor 0.5 that of the L-mode briefly and increases significantly. Note that measuremental error at a low density can contribute to this nonlinear behavior. The plasma density profiles in both L- and H-mode in SOL are continuation of the measured edge density at the LCFS (i.e., significantly higher density with long scale length in L-mode phase while extremely low density in H-mode phase).

It is important to investigate what happens to the plasma turbulence amplitude and spectra when the large-scale structure of turbulence is torn apart due to velocity shear or equivalent mechanisms. If the breaking of turbulence structures like streamer and ITG modes by the ErxB effect is responsible for reduced transport at the pedestal region, it is natural that the wave amplitude should be decreased in the region where the confinement is improved or vice versa. The nature of turbulence in plasma is wave-like, and the turbulence spectra can be represented as a superposition of all different wave numbers and frequencies as shown in Eq. 3.

It would be educational to compare the turbulence profiles in unnormalized ñ(r) together with the density profiles in the pedestal (Fig. 7a, c) and SOL (Fig. 7d, f) region. Here, ñ(r) (Fig. 7c, f) is deduced by multiplying the density profile (n(r)) to the ñ(r)/n(r) for both L- and H-modes. It is interesting to find the difference of the turbulence amplitude (ñ(r)) in the H-mode phase which is almost constant across the pedestal region while the amplitude (ñ(r)) in L-mode phase at LCFS is ~20–30% higher than that of the H-mode and gradually decreases to the same level as the H-mode. If the wave amplitude is constant across the pedestal region in the H-mode phase, it is fair to conclude that turbulence propagation may not be influenced by the mechanisms of the ErxB effect in the H-mode. The origin of the higher turbulence in the L-mode may be from inflow plasmas (i.e., high density and turbulence) as shown in the figures. In conclusion, drastic differences in the normalized turbulence level (ñ(r)/n(r)) between the L- and H-mode phases near the pedestal region are mostly due to density gradients of the L- and H-mode phases. A nearly constant ñ(r) level in H-mode may be the gradient-driven turbulence level in the H-mode in the absence of inflow plasmas. In the SOL region, both density and absolute turbulence level (ñ) are high in the L-mode and extremely low in the H-mode phase. This is consistent with the fact that high density and turbulence in SOL are a combination of inflow plasmas from unconditioned divertor plates, and increased outflow plasmas due to turbulence induced enhanced cross-field transport in the L-mode phase. When the inflow plasmas are reduced and the turbulence level is below a threshold value through divertor conditioning, the base cross-field transport (i.e., neoclassical transport) is recovered from anomalous transport. Here, the low density and turbulence represent the reduced outflow plasmas in the H-mode phase.

It would be an important exercise to consider how the inflow plasmas (density and turbulence) may be responsible for sudden changes in edge transport physics and/or different forms of edge pedestals such as QH-mode, I-mode, or edge of NT plasma. Here, the edge density is comparable to that of the L-mode, and temperature pedestal is comparable to that of the H-mode while the global edge pedestal plasma pressure is between H-mode and L-mode. The low edge plasma density in these confinement modes was attributed to enhanced particle transport at the edge. In the QH-mode and I-mode, coherent edge harmonic oscillation (EHO) and semi-coherent mode (Alfven modes) may play the role of turbulence in the L to H transition.

In toroidal devices, plasma density formation consists of ionization of neutrals at the LCFS by fuel injection and density part of inflow plasmas. The plasma density by gas injection is the main source, and density contribution from inflow plasmas may vary depending on divertor surface condition, but it is not the main contribution. Note that density increase by edge pellet injection can trigger H-mode edge and does not accompany high turbulence (i.e., short lived high turbulence during ablation time scale), whereas high turbulence level including blobs is maintained during high inflow phase.

This new transport model based on interplay between inflow and outflow plasmas can qualitatively explain many phenomenologies that we have struggled without fruitful results for the last half a century. They are applications to the physics of the H-mode, QH-mode, I-mode, edge of NT configuration, and transitions between all these improved edge modes routinely observed in diverted plasmas, even the threshold power for the H-mode transition. Complexity comes from various elements in many ways such as degree of divertor condition, ratio of turbulence and density in inflow plasmas, and enhancement of outflow density due to turbulence-induced anomalous transport. It is not difficult to understand that the edge pedestal height cannot be a universal, and variation is inevitable considering interplay between outflow and inflow plasmas in an edge magnetic configuration and materials of divertor in different devices. Also, this new transport model and concept of flow impedance can be applied to the edge confinement physics of double null system of tokamaks, as well as multiple x-points and island divertor system of stellarator to understand the inferior edge performance when x-points are increased in the system. Also, validation of this new transport model can help design effective divertor systems that can control inflow as well as outflow plasmas so that the stored energy can be maximized with the core plasma control.

5 Energy confinement time scaling laws and triple products as a measure of performance

5.1 Energy confinement time scaling laws for design of tokamak plasmas

One of the key performance measures of toroidal devices is the energy confinement time [τE = stored energy (J)/heating power (PH)]. Following a series of empirical studies of τE (mainly tokamaks and stellarators), scaling laws for τE were established with worldwide experimental data. The scaling study is a statistical regression study of the measured stored global energy confinement time against various device and plasma parameters, including the geometric factors as follows: major radius (R), minor radius (a), elongation (κ) and triangularity (δ), heating power (PH), plasma current (IP), plasma density (ne), and magnetic field (BT). For reliable statistical study, experimental designs with uncorrelated independent parameters are prerequisite. However, it is extremely difficult to interpret parameters as being dependent in real data. The degree of intercorrelation between independent parameters can easily change the exponents of independent parameters. Finally, a credible energy confinement time scaling law (ITER-89P scaling) [49] was established from L-mode data of worldwide tokamak devices before 1990 as shown in Eq. 4.

As H-mode operation became popular in various tokamak devices, a separate scaling study of H-mode data was performed. Since there were no clear criteria of H-mode discharge except higher edge pedestal accompanied by a signature of ELMs (i.e., dithering of Hα-light). Note that the appearance of ELM suggests that the edge pedestal is close to the edge pressure limit. The ITER-98Elmy scaling law [50] is shown in Eq. 5, and experimentally measured τE is plotted against that from regression in Fig. 8.

The parametric dependence of this scaling is not much different from ITER 89-P scaling law in Eq. 4 except for improved density and elongation dependence and worsened power dependence. The differences between these two scaling laws are reflected in the difference between L- and H-mode. Since one of the characteristics of H-mode is a higher pedestal density compared to that of L-mode plasmas, it is not surprising to find that density dependence is increased in ITER98 scaling. The heating power dependence is worsened due to reduced core heating as the edge density is increased. The increase of elongation dependence can be interpreted as an improved heating beam penetration. Of course, it is not true for ICRF and ECRH, but the data used for the H-mode scaling law is dominated by PNB heating system.

These two scaling laws were used as the basis of design tokamak devices such as ITER and DEMO as pursued by EU, China, Japan, and Korea, and confinement enhancement factor (H-factor) was used to adjust the design goal of confinement time. Note that it is critically important to understand the underlying physics of each independent parameter and intercorrelation between them. The most characteristic feature of the scaling laws is the size scaling as indicated in three different devices (JFT-2M, DIII-D, and JET) in Fig. 8, but only strong dependence appears on major radius (R) in both scaling laws (Eqs. 4 and 5). It is interesting to examine the geometric dependence of ITER-98 scaling (R1.39 and a0.58) with the data in this figure. Geometric data with the range of energy confinement time of these three devices are given in Table 1, and elongation is assumed to be more or less the same (i.e., κ~1.7) for these three devices. Wide variation in confinement time in each device is mainly due to variation in parameters other than geometric factors such as IP and PB.

Table 1 Range of τE from ITER98 scaling and geometric parameters shown for three devices (JFT-2 M, DIII-D, and JET)

| JFT-2 M | DIII-D | JET |

|---|---|---|

| τE ~ 20–50 ms | τE ~ 80–200 ms | τE ~ 300–900 ms |

| R ~ 1.30 m | R = 1.67 m | R = 3.00 m |

| a ~ 0.35 m | a ~ 0.67 m | a ~ 0.90 m |

| R/a ~ 3.7 | R/a ~ 2.5 | R/a ~ 3.3 |

| Vp ~ 4.8 m3 | Vp ~ 24 m3 | Vp ~ 90 m3 |

In order to examine the degree of intercorrelation between independent parameters of ITER98ELMy scaling, ratios of median τE data of the three devices (JFT-2M, DIII-D and JET) are compared with those of the geometric parameters (VP, Ra2, a0.58, and R1.38) as shown in Table 2. As shown in this table, correlation between the ratio data of τE and that of VP or Ra2 (assumed κ is the same) is excellent, while correlation with a0.58 and R1.38 data is poor. This is an example of regression results influenced by a strong intercorrelation between independent parameters.

Table 2 Ratios of the three device parameters are compared with those of median τE of each device from the ITER98 scaling. Plasma volume (VP) or Ra2 data are well correlated with the τE data, while R1.39 and a0.58 data from ITER 98 scaling have poor correlation with τE data. Here, the VP data includes elongation

| DIII-D/JFT-2 M | JET/JFT-2 M | JET/DIII-D | |

|---|---|---|---|

| τE | 4.0 | 17.1 | 4.3 |

| Vp | 5.0 | 18.8 | 3.8 |

| Ra2 | 4.7 | 15.2 | 3.2 |

| a0.58 | 1.46 | 1.73 | 1.17 |

| R1.39 | 1.41 | 3.20 | 2.25 |

The next strong dependence is IP scaling. Note that the range of IP data among devices is larger than the range within each device, and confinement is increasing at higher current in each device. Weak density dependence may be due to the spread of density in each device similar to that of different device sizes. The reason why BT dependence is weak may have to do with the fact that BT is slaved by Ip through edge q-value and vice versa. In the τE scaling law for stellarator where Ip is absent, BT has a strong correlation with τE.

It is important to realize that the confinement database in tokamak plasma is dominated by discharges with PNB heating power. Dependence of τE on PH (i.e., ~PH−0.5) is alike in each device, and it may have to do with saturation of the core heating power as PH is increased in each device. Note that the stored energy in the core ITB discharges is linearly proportional to the central PNB heating power (PH(0)). Also, the heating power used in this data is up to ~40 MW of the ion heating system (PNB system), while the highest electron heating power applied is less than ~10 MW and central heating is dominant due to the resonance layer. Note that the scaling laws do not distinguish the heating methods (i.e., electron or ion heating). The consequence will be fatal in the design of the device if the choice of heating method is not consistent with the data used in the scaling law.

5.1.1 Triple product (niτETi) as a measure of fusion power

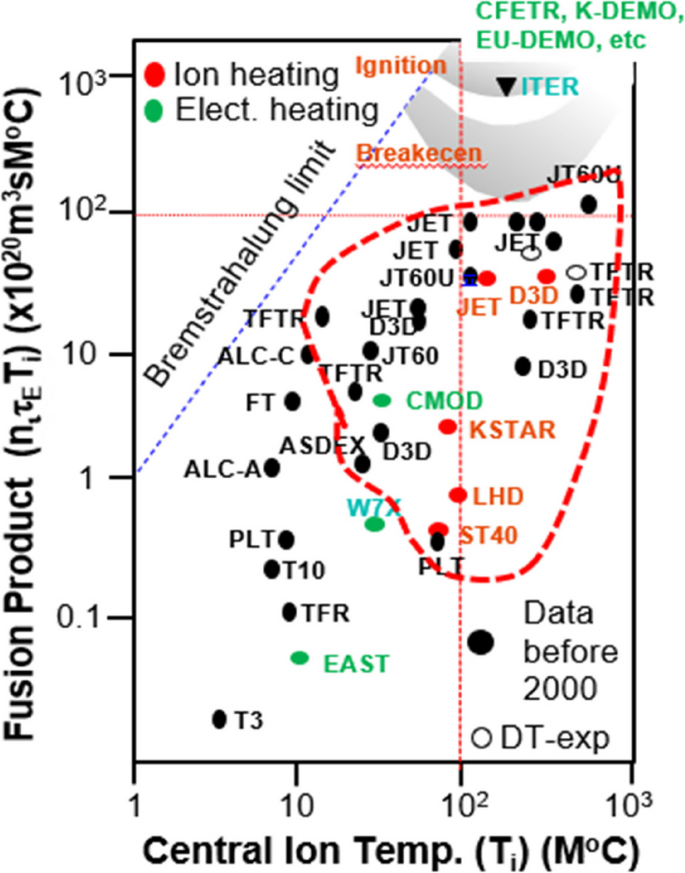

The most direct performance measure of toroidal device is the triple product (niτETi) which is equivalent to Q (= PF/PH) for discharges with Ti>Te, where PF is fusion power from DT and DD experiments including three large tokamaks (e.g., TFTR, JET, and JT-60U). Representative performance of each device (niτETi) for the last half a century is shown against ion temperature (Ti) in Fig. 9. There are a few important points to make in the course of achieving ignition regime and beyond based on this data:

1) Performance data (black circles) from T3 tokamak (1950s) to high-performance data of the three large tokamaks (1990s) is based on a short pulse device with Cu magnets. New performance data after the late 1980 s including data from superconducting devices such as the EAST, W7-X, KSTAR, C-MOD, and recent JET results up to 2023 are marked with red circle (PNB) and blue box (ECRH and ICRF).

2) High-performance data with DT and DD with Ti > ~8 keV are with PNB heating system (red dotted boundary), and C-MOD data (blue color) is the highest results with electron heating system thus far. In order to approach the ignition regime, a ×10 improvement on the best niτETi data is the goal.

3) It is risky to approach the ignition regime with an electron heating system alone, since there is no single data point above Ti~10 keV so far.

Performance data accumulated for the last half a century is illustrated. The y-axis is niτETi (≅ Q for Ti > Te), and the x-axis is ion temperature (Ti). Data with black circle is up to year 2000 including the highest performance data from three large tokamaks (TFTR, JT-60U, and JET). Projection of ITER in ignition territory is shown together with other large devices (CFETR, EU-Demo, and K-Demo). New data points after year 2000 are shown; green data points are discharges heated by ECH and/or ICRF (electron heating: Te > Ti), and the red circles are discharges heated by PNB system (ion heating: Ti > Te). Territory with red dotted lines is discharges heated by PNB system

The performance of stellarator plasmas is similar to that of tokamak. When LHD adopted a PNB system (~50 keV) after a long struggle with NNB at ~250 keV (i.e., electron heating system), a discharge with Ti~10 keV was demonstrated [51], whereas the W-7X [34] has not achieved ion temperature above ~10 keV. Furthermore, apparent physics issues of Ti clamping [36] and density pump-out [52] with electron heating systems alone do not have solutions yet.

As illustrated in Fig. 9, performance improvement up to “scientific breakeven” condition (Q~1) was almost reached with direct ion heating (PNB) alone in JET, TFTR, and JT-60U. ITER design evolved from a large plasma volume (Vp) larger than ~2000 m3 (i.e., design based on earlier L-mode confinement time scaling) to a smaller volume (Vp~900 m3) using ITER98-Elmy H-mode scaling law (Eq. 5) that is dominated by data with PNB system. The projected energy confinement time will be five times higher than the best τE of the JET data as shown in Fig. 8. Operation of the plasma with a reasonably high density (> 1.0 × 1020 m−3) and ion temperature above ~10 keV can achieve the design objective of Q = 10 (PF~500 MW) on ITER. Since, there is no single example of ion temperature above 10 keV with the electron heating system alone, it would be wise to wait until test of substantial electron heating experiments up to ~35 MW on DTT, Italy [53], first so that unexpected problems reaching high ion temperature, Ti > 10 keV, can be resolved before ITER adapts ~80-MW ECRH power.

Note that ITER as well as ARC are only equipped with electron heating systems alone, and it would be a challenge to achieve a regime that can produce sufficient α-power to sustain the ignited plasmas above Ti > 10 keV. The engineering aspect of the electron heating system for these devices is even more challenging. Operation of gyrotrons and wave antennas to deliver substantial heating power for ITER (~80MW ECRH) is a monumental task in addition to physics issues of electron heating such as the density pump out and Ti clamping. These concerns will be shared with all large fusion devices like BEST, CFETR, EU-DEMO, and K-DEMO.

6 Perspective of ignition in magnetic fusion and most probable compact ignition tokamak plasma

6.1 Perspective of ignition in magnetic fusion

Among magnetic fusion devices, closed system such as tokamaks and stellarators is more favored over open system like magnetic mirror, due to their better performance in energy confinement in general. The intrinsic energy loss mechanism in an open system such as the axial loss in the mirror device is difficult to overcome. Among closed magnetic devices, performances of tokamaks and stellarators showed more promise than others such as field-reversed configuration (FRC) or spheromak. As discussed in earlier sections, core improved confinement (ITB) of the closed magnetic surface shares the same actuator (i.e., heating profile), but edge confinement can be different with different edge magnetic configurations (i.e., single to multiple x-points). The edge confinement of tokamak plasmas has an advantage (i.e., high flow impedance) over stellarators (i.e., low flow impedance) unless the system can deduce the x-points. Stellarators do not require a driven plasma current, while tokamaks and other closed devices require a plasma current (poloidal or toroidal) to achieve equilibrium. But this very plasma current for stable equilibrium can also induce harmful MHDs and lead to disruption. For continuous operation of these devices, an external current source is required. If the goal is a demonstration of ignition plasma in a magnetic fusion, tokamaks may be the best choice for now. Note that superior energy confinement of the tokamak approach undermines issues of instability and current drive which are essential for steady-state operation. For this issue, the stellarator configuration that does not depend on plasma current has potential for achieving steady state in fusion devices if the inferior confinement issue (i.e., poor edge magnetic configuration) and complexity of hardware can be resolved.

After three large tokamak eras, devices based on superconducting magnets such as KSTAR, EAST, and LHD and W7-X were constructed to challenge a steady-state operation expecting an efficient external current drive source which has yet to come for tokamaks. The initiation of an international effort (i.e., ITER) to go beyond scientific breakeven took a long time. The current ITER project to demonstrate an “ignition state” and a “tritium breeding test” is in progress, but future perspectives depend on resolving uncertainties of electron heating and engineering issues. Now fusion energy development efforts by private sectors are active, with representative ones including CFS/MIT, USA, and Fusion Energy, UK. A plasma device size comparable to JET class (VP~90 m3) may not be able to achieve the ignition, and even devices like ARC and JT60-SA (VP~140 m3) may only marginally achieve the ignition state due to short falls in energy confinement time. Most large fusion devices like K-DEMO [7], EU-DEMO [6], and CFETR [5] including ITER have been designed with the plasma volume more than VP~900 m3 and may have potential in surpassing the ignition state, but there is no clear path for high plasma density operation at ion temperature above ~10 keV with electron heating systems such as ECRH and ICRF in such a large device.

6.1.1 Most probable ignition test device for magnetic fusion

The first step would be estimation of a plasma volume for fusion power which can produce sufficient α-power to sustain the ignition state. The plasma volume is based on the energy confinement time scaling as demonstrated in the previous section. The target τE can be ~2.4 s assuming the discharge has an enhancement factor (H-factor) of ~1.5. Then, the equivalent H-mode confinement time (i.e., ITER-98) is ~1.6 s. Using the plasma volume (VP~90 m3) of the JET device which has a median value of τE~0.6 s as shown in Fig. 8, the equivalent plasma volume (VP) can be ~240 m3. Note that the plasma volume can be further reduced to ~180 m3 if a long confinement time (~0.9s) in JET data and a high-density operation is adapted.

Second, design of optimum ion heating systems (combination of on-axis and off-axis beam lines) for effective core heating to achieve the best H-factor possible as well as high ion temperature. Good references are high-performance discharges demonstrated in JT-60U and the “super H-mode” in DIII-D. In a moderately large plasma (i.e., Vp < 300 m3), optimization of core heating can be achieved utilizing plasma geometric factors, edge density, and injection angles of PNB system. In the early design phase, various shapes of equilibrium (i.e., D-shape and reverse D shape with high elongation and racetrack) should be considered without compromising essential edge magnetic configuration. The choice of the plasma minor radius (a~1.2 m) is only slightly larger than that of the JET device where ~90-keV PNB was successfully used for improved core confinement regime (Ti>Te). Therefore, PNB power up to ~40 MW at the beam energy of ~120 keV can be a good target. The heating beam source at ~120 keV with minimum 1/2 and 1/3 energy components would help the core heating. For effective core heating at high-target density plasmas, the injection angles and plasma geometry can be optimized. An extensive MHD stability study for stable pressure profiles should be performed to accommodate optimum core heating.

Finally, the most important task is controlling the pedestal density of the plasma through a smart divertor system so that a high edge confinement mode is sustained while core heating is allowed. Note that the density limit in tokamak plasmas is purely empirical (i.e., Murakami limit, Greenwald limit). Operation of the plasma density ~1.5 × 1020/m−3 in moderate plasma volume (~240 m3) is a reasonable approach, since the core density of the “supershot” in TFTR was >~1 × 1020 m−3. The initial ignition state can be reached at a slightly low density with external heating, while α-power is increasing. Once the ignition state is achieved, fueling rate can be slowly increased while the PNB system can be closed.

Using τE~2.4 s, ne~1.5 × 1020 m−3, and Ti~15 keV (Q~5–6 with PNB power of ~40 MW), the initial fusion power will be ~220 MW with an α-power of ~45 MW which may be adequate to test the initial ignition state with ion temperature ~15 keV. Note that these numbers are for guidance purposes only, and there will likely be deviations from operating plasma pressure and external heating power. Additionally, there is large uncertainty with respect to transition of external and internal heating source, and the α-power of ~45 MW may be a very conservative side. Also, an improved H-factor above ~1.5 can provide more fusion power ~300 MW at smaller device size (VP < 200 m3). A successful operation of the ignition state warrants demonstration of electricity generation so that the fusion energy can be a potential practical energy source for mankind.

7 Summary

The concept of flow impedance, based on inflow/outflow plasmas between the LCFS and divertor, qualitatively explains edge confinement characteristic of tokamaks and stellarators. The interplay between inflow and outflow plasmas thus may be responsible for the edge of the L-mode and H-mode as well as transitions between two modes. Here, the turbulence part of the inflow plasmas from a divertor may provoke cross-field anomalous transport of the outflow plasmas, and density part contributes to the edge plasma density. Similarly, EHO or Alfven modes at the edge of QH-mode and I-mode can play a similar role of turbulence. A smart divertor system design is critical for control of turbulent inflow plasmas and effective heat dissipation as an edge control actuator. The actuator for core confinement can be an effective core heating system for ions until issues of electron heating system are resolved. The plasma volume is primarily determined by energy confinement time scaling study, and direct ion heating with PNB power of ~40 MW will be effective in sustaining plasmas with Ti > 10 keV at moderately high plasma density of ~1.5 × 1020/m3. The most probable compact tokamak plasma with volume of ~240 m3 can validate transition physics from external heating to α-heating as suggested. The fusion power estimated to reach ~220 MW (Q~5–6) with an α-power of ~45 MW, thus demonstrating a potential electricity output of ~100 MW.