Abstract

The Electron-Ion Collider (EIC) is the world’s first electron + heavy-ion collider, and also performs polarized electron + polarized proton and light ion collisions, that will be constructed at Brookhaven National Laboratory in the USA. It will explore new areas of quantum chromodynamics (QCD) and foster the richness of nuclear and hadron physics. The EIC program will produce many new and very extensive results in nuclear and hadron physics over the next few decades. As an international cooperation project, it is essential for the future development of this field in Asia to focus on taking the lead in this EIC project.

1 Introduction

The Electron-Ion Collider (EIC) [2] is the most advanced accelerator whose main purpose is to precisely study the still poorly understood gluon behavior inside nuclei and nucleons (protons and neutrons). It is the world’s first electron + heavy-ion collider, and also performs polarized electron + polarized proton and light ion collisions. It will be constructed at Brookhaven National Laboratory in the USA and is scheduled to start operation around 2032.

The EIC will explore new areas of quantum chromodynamics (QCD) and foster the richness of nuclear and hadron physics. The major goal of physics research at the EIC is to provide answers to three major academic questions:

How does the mass of the nucleon arise? Symmetry breaking generates mass. The Higgs mechanism accounts for only about 1% of the mass of the nucleon. The rest of the mass emerges from quark-gluon interactions. The EIC will investigate the origin of the other 99% of mass generation, especially determines an important term contributing to the nucleon mass, the so-called “QCD trace anomaly”.

How does the spin of the nucleon arise? The spin is one of the fundamental properties of particles. Nucleon spin cannot be explained by a static picture of the proton and the spin of quarks carries only about one-third of the spin of the nucleon. We will measure the different contribution from the quarks, gluons and orbital angular momentum at EIC.

What are the emergent properties of high-density gluon system? It is known that nucleons at high energies are occupied with small momentum gluons. Gluon saturation is a new state of matter at extreme high densities at the high-energies inside nucleons and nuclei, where the production of gluons and their recombination balance out. We will discover the gluon saturation and evaluate the properties at EIC.

With the increase in achievable energy and luminosity due to advances in accelerator technology, it has become possible to study the internal structure of the nucleon in finer detail. Figure 1 shows a view of the EIC accelerator complex. In the EIC accelerator design, the proton beam is accelerated up to 275 GeV and the electron beam is accelerated up to 18 GeV. The maximum center-of-mass collision energy of the EIC is 140 GeV for electron-proton. The maximum luminosity for electron-proton is 10\(^{34}\)cm\(^{-2}\)s\(^{-1}\). The maximum EIC collision energy of 140 GeV is not as high as the collision energy of HERA, an electron-proton collider that existed in the past, 318 GeV, however the EIC has 1000 times higher luminosity than HERA.

The EIC also has the following unique features. Whereas HERA’s proton beam was unpolarized, both electron and proton beams are polarized in the EIC. Furthermore, while HERA’s hadron beams are only proton beams, the EIC can accelerate not only protons, but also polarized light ions and heavy ions. In addition, the collision energy can be varied widely. In other words, it is an extremely versatile accelerator that can observe a wide range of nuclides, both unpolarized and polarized, with a wide range of kinematics. Ion beams are accelerated to 110 GeV per nucleon in laboratory system energy. The maximum center-of-mass collision energy of the EIC is 90 GeV per nucleon for electron-nucleus.

Physicists from many Asian countries have long been interested in the EIC and have supported and cooperated with the EIC program in various ways. In 2015, a letter of interest from Asian countries was submitted to the U.S. Nuclear Science Advisory Committee (NSAC) when the EIC program was discussed in the long-range plan. Starting in 2022, the EIC Asia Workshops are being held in Korea in 2022, Japan in 2023, and Taiwan and China in 2024, with guests from the USA invited to discuss international cooperation. Monthly EIC Asia Group meetings via remote connection have started in 2023. Cooperation in the geographically close Asian region has great benefits for detector development and construction. We would like to continue to develop efficient cooperation in the Asian region with the participation of more Asian countries.

2 Physics at EIC

Nucleons are made of quarks and gluons. In the high-energy experiments conducted at EIC, nucleons and nuclei are composed of quarks and gluons and are interpreted theoretically based on perturbative QCD. The internal structure of nucleons and nuclei is investigated by deep inelastic scattering of electrons. The structure function can be examined as a two-variable function of the momentum fraction (x) carried by the partons (quarks and gluons) and the square of the four-momentum transfer q, \(Q^2 = -q^2 (>0)\), which can then be examined as the parton distribution function, a one-dimensional momentum distribution for quarks and gluons, respectively. The fineness of the nucleon’s internal structure is expressed as x, and is now measured over a range of four orders of magnitude. In the small x range, the gluon density increases and the probability of gluon involvement in a reaction is high.

We will focus on what is still poorly understood about gluons in this era of high-energy QCD development, and the physics that EIC is trying to unravel. Using gluons as a key to a new understanding of the internal structure of nucleons and nuclei, we explore the confinement of quarks and the origin of mass.

2.1 Spatial distribution inside nucleons and nuclei

The EIC extends quark-gluon structure inside the nucleon and nuclei, which has been studied in one dimension, to three dimensions. By selecting specific exclusive final states in electron+proton (e+p) and electron+nucleus (e+A) collisions, the EIC can precisely measure the transversely extended distribution functions of quarks, antiquarks, and gluons.

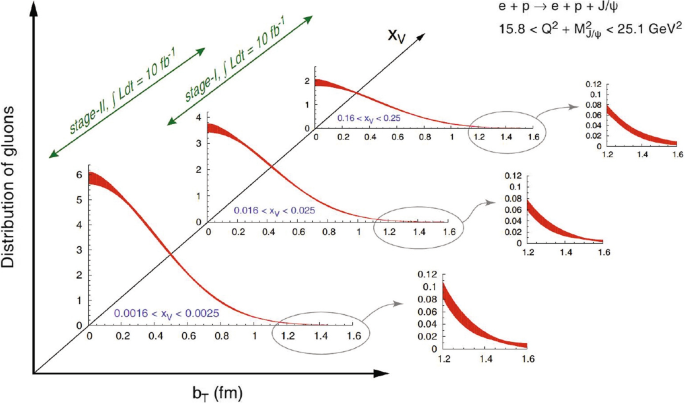

Transverse spatial distribution of gluons obtained from the exclusive \(J/\psi\) production cross section and its predicted precision. The width of the band represents the expected precision. The graph on the right depicts the \(b_T\) = 1.2–1.6 (fm) portion of the graph on the left, with the vertical axis expanded

Figure 2 shows the transverse spatial distribution of gluons obtained from the exclusive \(J/\psi\) production cross section and its predicted precision [3]. The precision includes systematic and statistical uncertainties in the extrapolation to the unmeasured region for the momentum transfer of scattered protons. The position of the gluon relative to the proton center is denoted by \(b_T\) (fm), and \(x_V\) is the kinematically determined fraction of the gluon’s momentum.

2.2 Origin of nucleon mass generation

One of the main goals of physics research at EIC is to determine the origin of mass of hadrons (protons, neutrons and mesons), which are responsible for most of the mass of visible ordinary matter. In the history of the universe, the generation of the Higgs field is known as the origin of mass, but the mass resulting from this is only about 1% of the current mass of ordinary matter in the universe. The remaining 99% of the mass originates from the confinement of quarks that occurred after the Higgs field generation in the history of the universe. However, no clear explanation has yet been given as to the mechanism by which this mass is obtained.

The mass of hadrons is thought to be due to an unresolved quark confinement mechanism inside hadrons, and the collision experiments of polarized electrons and polarized protons at EIC will study this origin by dividing it into the emergent contribution of the respective energies of the quarks and the gluons and the contribution from their condensation. This can be further clarified by studying the origin of mass for different hadrons, protons and mesons, to differentiate their emergent contributions. This is because the quark and gluon energies and condensation contributions are thought to be quite different for protons and mesons. The quark-gluon structure of nucleons, hadrons, and nuclei has been studied in studies of the origin of mass. At EIC, in addition to the one-dimensional structure with respect to the collision axis, the structure is extended transversely to the collision axis and examined as a three-dimensional structure including orbital motion and other degrees of freedom. This requires the detection of processes that exclusively measure all particles produced in collisions and coherent diffraction processes. By measuring these processes, it is possible to obtain the form factor of the energy-momentum tensor and to know the mass and pressure distribution of quarks and gluons inside nucleons and nuclei [6].

2.3 Origin of the nucleon spin

The nucleon spin (1/2) consists of the spin of the quark and antiquark (\(1/2\cdot \Delta \Sigma\)), the spin of the gluon (\(\Delta G\)), and the orbital angular momentum of the quark and antiquark (\(L_z^{q,\bar{q}}\)) and gluon (\(L_z^g\)).

Measurements in the small x region are now essential for the accurate determination of the polarized gluon distribution \(\Delta g(x)\), which represents the contribution of the gluon spin to the nucleon spin.

As HERA played a major role in the determination of the unpolarized gluon distribution g(x), it is also important to measure the polarized gluon distribution \(\Delta g(x)\) not only in the x but also in the wide \(Q^2\) region. The world’s first collider experiment of polarized DIS with polarized electron and proton beams at the EIC will enable measurements at small x and large \(Q^2\), similar to what HERA has achieved for unpolarized distributions. A global analysis of the results of the polarized distribution measurements with fixed target experiments, the results of the polarized proton-proton collider experiment at RHIC, and the polarized distribution measurements at EIC will reveal the flavor spin structure of polarized nucleons with a high accuracy.

Furthermore, the EIC extends the quark-gluon structure inside the nucleon, which has been investigated in one dimension, to three dimensions. This allows us to correlate spin and orbital motion, to understand the orbital motion of quarks and gluons with respect to nucleon spin, to determine the contribution of orbital angular momentum to nucleon spin, and to complete our understanding of nucleon spin.

2.4 Emergent properties of the high-density gluon system

The understanding of nucleons and hadrons also applies to nuclei, leading to a new understanding of the quark-gluon picture of nuclei. Of interest here is the small x region, where gluons carrying a small fraction of momentum are thought to be saturated inside nucleons and nuclei. Experimental exploration of this region is also important for understanding the initial conditions for the generation of unconfined quark-gluon plasma (QGP) produced in high-energy heavy-ion collisions.

At low x, the rise in gluon density is suppressed by the nonlinear process of gluon recombination, and at a certain \(Q_s\) scale, gluon branching and recombination reach equilibrium and the gluon density saturates. Such gluon saturation, called Color Glass Condensate (CGC), is a consequence of gluon self-interaction in QCD. For measurements in that region, we need a high-energy, high-luminosity EIC that can measure the low x region at a sufficiently high \(Q^2\) or resolution. In order to know what kind of gluon or quark-antiquark state is formed as a result of saturation, the region must be clearly separated and measured. This is a new experimental method to study confinement at high \(Q^2\).

Reaching \(Q_s\) requires several TeV as the center-of-mass system energy in electron-nucleon scattering, but by using nuclei, an increase of \(A^{1/3}\) is obtained, where A is the mass number of the nucleus and \(Q_s\) can be reached at lower energies. In the EIC accelerator design, ion beams are accelerated to 110 GeV per nucleon in laboratory system energy. The nucleus, moving at nearly the speed of light, becomes a thin disk rather than a sphere due to relativistic effects. Therefore, the gluon density per transverse plane of the nucleus increases in proportion to the diameter of the nucleus, or \(A^{1/3}\). The larger the beam of nuclei with A, the lower the collision energy can reach \(Q_s\), where the gluon saturates, while ensuring that \(Q^2> 1\)(GeV/c)\(^2\), which allows for a perturbation theory interpretation.

e+p collisions require access to the \(x < 10^{-5}\) level to reach \(Q_s\), which requires several TeV in collision energy. While the observation of gluon saturation could not be established with HERA, which is superior in terms of collision energy, the EIC can reach the kinematics where saturation is expected by e+A collisions. Although HERA, RHIC, and LHC provide hints for gluon saturation, the e+A collisions in EIC provide unambiguous evidence, and it allows us to explore a new area of collective dynamics of saturated gluons.

Diffraction events in e+A collisions are a promising way to establish the existence of gluon saturation and to study its underlying dynamics. In coherent diffraction events, the protons and nuclei remain intact after the reaction, and the particles produced in the reaction are separated from the protons and nuclei by a large region free of produced particles. In HERA e+p collisions, these types of diffraction events accounted for a large fraction of the total cross section (10–15%). The gluon saturation model predicts that more than 20% of diffraction events occur in EIC e+A collisions. Simply speaking, the diffraction cross section is proportional to the square of the gluon distribution, making it very sensitive to the gluon saturation. Measurements of coherent diffraction showing interference with nuclei in e+A collisions at EIC will provide clear evidence of the gluon saturation.

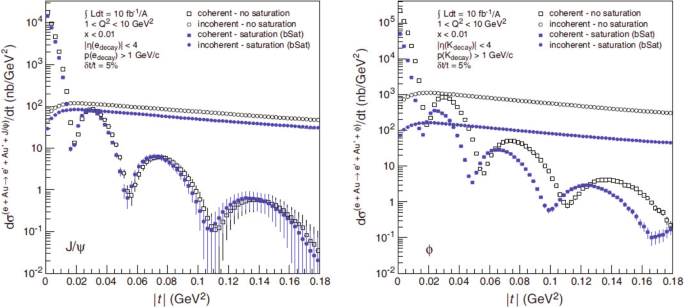

Cross sections for the exclusive production of \(J/\psi\) (left) and \(\phi\) meson (right) in coherent diffraction events showing interference with nuclei from e+A collisions, and incoherent diffraction events where nuclei break up showing no interference. Predictions from saturated and non-saturated models of gluons are shown

Exclusive vector meson production in diffraction events is the cleanest process because the number of particles in the final state is small. Figure 3 shows cross sections of \(J/\psi\) on the left and \(\phi\) mesons on the right [3]. Coherent diffraction events show the form of colliding nuclei. Coherent diffraction events can be distinguished from incoherent diffraction events, in which the nucleus breaks up and shows no interference, by detecting the neutrons emitted from the break-up. For \(J/\psi\), which has a smaller radius than \(\phi\), there is little difference between the gluon saturation model and the non-saturation model, but for \(\phi\), there is a significant difference.

3 ePIC international collaboration experiment and ePIC detector

The ePIC (Electron-Proton/Ion Collider) international collaboration was formed in 2022 to design, build and operate the first experiment and detector in the EIC. It will build the world’s most powerful particle detector for analyzing collisions between electrons and protons and other nuclei. The key physics in the EIC and the detector that will achieve the physics goals were conceptually designed in 2020 as an activity of the EIC User Group and reported in a Yellow Report [2].

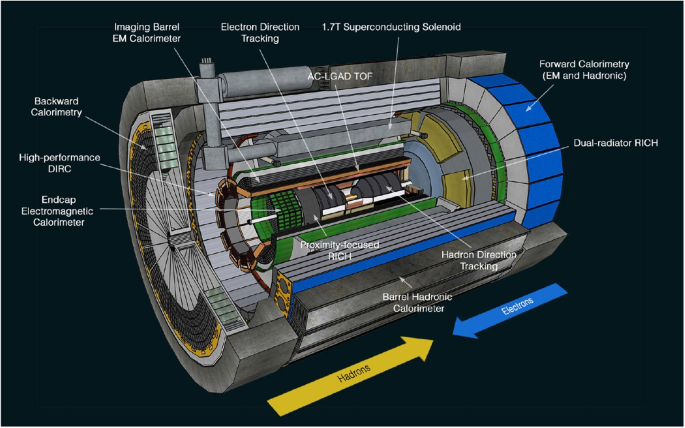

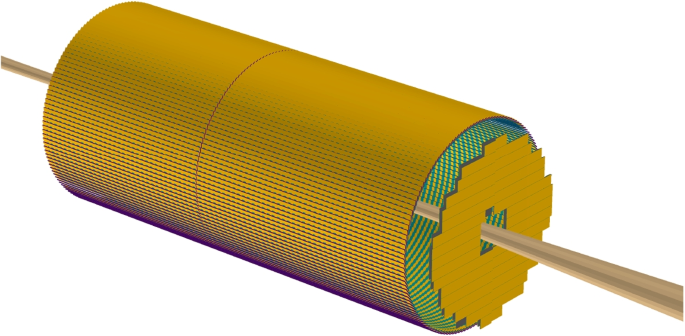

Figure 4 shows a cutaway view of the ePIC detector. The detector concept integrates cylindrical central detectors and additional detectors located along the EIC beamline. It is designed to detect particles produced by reactions at the collision point of the beams as close to the beamline as possible. The central detector consists of a 1.7 Tesla superconducting magnet and a barrel detector covering the side of the cylinder, a forward detector covering the hadron beam direction, and a backward detector for the electron beam direction. Each detector consists of tracking detectors to detect charged particles, detectors to identify the type of particles, and calorimeters to measure particle energies as an electromagnetic shower and hadron shower. All data from these detectors are processed by the streaming data acquisition system, and analyzed and recorded by the computer system in the latter stage.

4 Collaboration in Asia

In this section, we describe the contributions made by the cooperation of Asian countries to some of the detectors of the ePIC experiment.

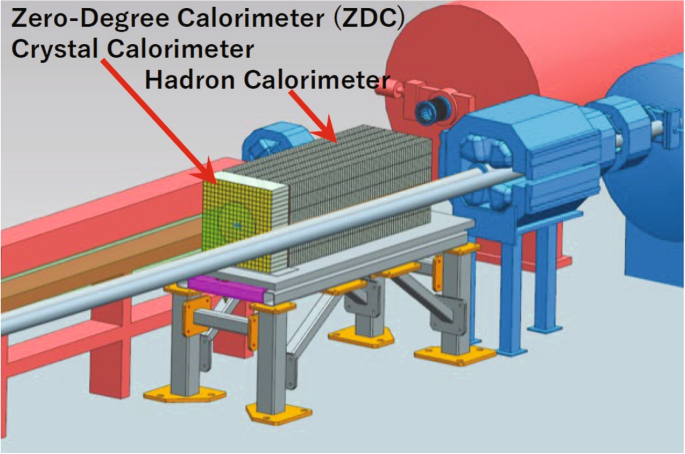

4.1 Zero-degree calorimeter

The Zero-Degree Calorimeter (ZDC) is a calorimeter located in the direction of the hadron beam, about 35 m far-forward from the beam collision point between the hadron and electron beam lines, where only the neutral particles, mainly neutrons and photons, produced in the collisions are detected. ZDC design is currently underway with a crystal scintillator as an electromagnetic calorimeter and a multilayer hadron calorimeter with iron as absorbing layer and plastic scintillator tiles read out by SiPM (silicon photomultiplier). Figure 5 shows the ZDC located between the hadron and electron beam lines.

ZDC plays a major role in the study of the mass of mesons in addition to protons [5]. This is because the detection of neutrons and \(\Lambda\) particles at ZDC makes it possible to study the internal structure and origin of mass of the mesons that are produced as their partners. Since it is considered that protons and mesons have completely different contributions from quark and gluon energies and condensation, the difference in their emergent contributions can be clarified.

In the study of the origin of mass at EIC, the quark-gluon structure of nucleons, hadrons, and nuclei is investigated not only as a one-dimensional structure with respect to the collision axis, which has been studied so far, but also as a three-dimensional structure extended transversely to the collision axis and including degrees of freedom such as orbital motion. This requires the detection of processes that exclusively measure all particles produced in collisions, and also requires coherent diffraction processes.

In EIC, ZDC has the ability to detect spectators, recognize coherent diffraction events in e+A collisions, characterize the collider for each event using neutron multiplicity in e+A collisions, study the origin of mass, and perform many other roles. ZDC is one of the most important detectors to ensure exclusive and coherent diffraction processes. Incoherent events can be isolated by identifying the break-up of the excited nucleus. The evaporated neutrons produced from the break-up in the diffraction process can be used in about 90% of the cases to separate coherent processes. In addition, photons from the de-excitation of the excited nuclei can help identify incoherent processes even in the absence of evaporated neutrons.

4.2 Barrel TOF-PID detector

As for the particle-ID (PID) performance of the ePIC detector, a 3-sigma separation of pions, kaons, and protons in the pseudo-rapidity (η) region of \(|\eta | < 3.5\) is required to achieve the physics. The key to understanding the origin of the mass of matter is the measurement of the gluon contribution responsible for the mass. This requires the measurement of various meson production processes, and the detection of mesons is done using the identification of separated pions, kaons, and protons.

The detector responsible for PID for low momentum around 1 GeV/c is the TOF-PID detector, which performs PID by time-of-flight (TOF) measurement. The AC-LGAD (low-gain avalanche diode) detector is used as the TOF-PID detector in the barrel and forward detectors. A time resolution of 35 ps is required for the barrel TOF-PID (BTOF) for the barrel detector and 25 ps for the forward TOF-PID (FTOF) for the forward detector. Figure 6 shows geometries of BTOF and FTOF. The Asia Group is responsible for the development, construction, and operation of this BTOF detector. The BTOF detector covers an overall area of 12 m\(^2\) and consists of a 0.5 mm \(\times\) 10 mm strip readout AC-LGAD detector with a 2.4-M channel.

The development of the AC-LGAD sensor has so far been carried out by the eRD112 of generic EIC-related detector R&D program. Prototypes have been made at HPK (Hamamatsu Photonics K.K.) and BNL and beam tested at FNAL. The strip type sensor at BTOF will now be taken over by the Asian region, mainly by the Japan group, and discussions are underway with HPK for the next prototype to be built in 2025. For the pixel type sensor, the EICROC under development will be used as the readout ASIC, and output from 10-bit TDC and 8-bit ADC will be obtained. For the BTOF strip type sensor, the capacitance is different from that of the pixel sensor, so we are discussing the development of other ASICs. In addition to this, we will develop a stave with a long readout line to integrate the sensor and ASIC to form the entire detector. AC-LGAD requires tight temperature control, and the cooling system must be designed under tight material restrictions as well. The design of the mechanical support for the entire detector is also underway.

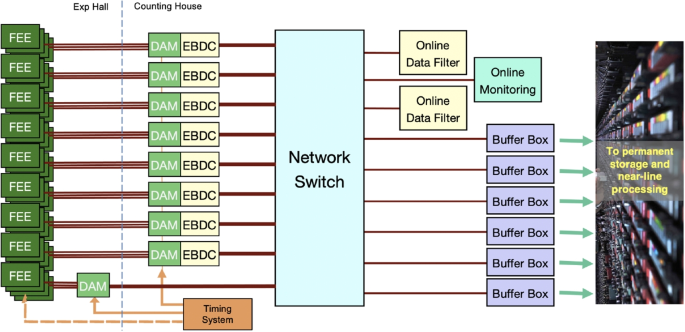

4.3 Streaming DAQ and computing

EIC will deploy new paradigms in large scale nuclear experiments. Since the expected luminosities will reach up to 10\(^{34}\) cm\(^{-2}\)s\(^{-1}\), EIC will produce an extremely large data sample to be processed. Recent developments in collider experiments such as LHCb and ALICE have shown the benefits of near real-time analysis [1, 4]. Based on those developments, the ePIC collaboration will implement an flexible, scalable, and efficient streaming data acquisition system. The deployment of the streaming readout system will provide the advantages of replacing custom level-1 trigger electronics, using computing, virtually deadtime-free operation, and the opportunity to study event selection in greater detail. The ePIC detector will consist of around 24 detector subsystems using different several readout technologies which include Silicon Monolithic Active Pixel Sensors (MAPS), Low Gain Avalanche Detectors (AC-LGAD), High Rate Picosecond Photodetectors (HRPPDs), and Silicon Photomultiplers (SiPMs). A schematic of the ePIC readout scheme is shown in Fig. 7. Each digitized signal is streamed from the detectors with a time-stamp that uniquely identifies its position on the time domain. This time-stamp is used to aggregate the information from all detectors and to build “time-frame”, which corresponds to the picture of the whole detector taken at a certain time. Each frame is then streamed to online computing farm where CPUs and hardware accelerators such as GPUs and FPGAs perform prompt reconstruction, apply a selection algorithm, and create a software “trigger” to decide if an objective “event” is present in the time-frame and deserves to be further reconstructed. Then, those “time-frame” data is further streamed into dedicated computing facilities to allow the full reconstruction. The full reconstruction of an “event” requires to apply the detector’s calibration and alignment into the reconstruction pipeline. The first set is obtained by processing a short amount of data taken during the commissioning. More precise evaluation of calibration will be performed using production runs and dedicated workflows will be implemented in the prompt reconstruction. The global timing distribution system will be crucial for the streaming readout to ensure that the data from different detectors can be synchronously aggregated. This will be provided based on a copy of the accelerator bunch crossing clock (running at 98.5 MHz). A subset of these systems will require a jitter on the order of 5 ps in order to realize required timing resolutions for the fast timing and time-of-flight detectors (20–30 ps).

The maximum interaction rate at the EIC is expected to be 500 kHz. The expected data rate off the detector is O(100 Tb/s) and digitized data off the detectors will be aggregated in the PCIe-based data aggregation boards (DAM) and filtered data by FPGA on the DAM will be sent to the online farm (Echelon1) in host labs (BNL and Jefferson Lab) at the rate at O(10Tb/s). Each online farm node represents a multi-core server with minimally support 32–64 cores and will support PCIe-based GPUs and/or FPGAs. Further filtered data or prompt reconstructed data will be sent to the distributed computing facilities in various countries (Echelon2) for the full reconstruction. The high performance network between counting house, Echelon1, and Echelon2 is expected to support 100/400 Gbps bandwidth connections based on the ESnet network funded by DOE Office of Science. In the next few years, we will start development of streaming framework, online processing workflows, and those orchestration, including workload management. We are going to build small-scale testbench and will start full chain tests of streaming from Echelon0 to Echelon2.

5 Conclusions

We have been working for a decade to stimulate Asian participation in the U.S. EIC program. We are working to further promote cooperation toward the realization of the program, the completion of the accelerator and detector, and the start of the physics program. The USA has asked the international community to contribute a certain percentage to the EIC program as an international cooperation project, and discussions and concrete work are underway with Asian nations accordingly.

The EIC program will produce many new and very extensive results in nuclear and hadron physics over the next few decades. Currently, the only facilities in Asia that promote nuclear and hadron physics are those in the low- and intermediate-energy regions, while those in the high-energy regions have to rely on facilities in Europe and the USA. Therefore, as an international cooperation project, it is essential for the future development of this field in Asia to focus on taking the lead in this EIC project.

Data availability

Data and materials used in this article were obtained from publicly available information and articles for which citations are provided.

References

-

R. Aaij et al., A comprehensive real-time analysis model at the LHCb experiment. JINST 14(04), P04006 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-0221/14/04/P04006

-

R. Abdul Khalek, et al., Science Requirements and Detector Concepts for the Electron-Ion Collider: EIC Yellow Report. Nucl. Phys. A 1026, 122447 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2022.122447

-

A. Accardi et al., Electron Ion Collider: the next QCD frontier: understanding the glue that binds us all. Eur. Phys. J. A 52(9), 268 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/i2016-16268-9

-

S. Acharya et al., ALICE upgrades during the LHC long shutdown 2. JINST 19(05), P05062 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-0221/19/05/P05062

-

A.C. Aguilar et al., Pion and kaon structure at the electron-ion collider. Eur. Phys. J. A. 55(10), 190 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/i2019-12885-0

-

X.D. Ji, A QCD analysis of the mass structure of the nucleon. Phys. Rev. Lett. 74, 1071–1074 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.74.1071

Acknowledgements

The content of this article is derived from the accumulation of numerous international collaborators of the EIC user group and the ePIC experiment. We thank all these international collaborators.

Funding

No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This article was primarily written by the corresponding authors with input from contributing authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.